SCI Pamphlets: Staying Healthy after a Spinal Cord Injury

The pamphlet series:

• Taking Care of Pressure Sores

• Maintaining Healthy Skin (Part I)

• Maintaining Healthy Skin (Part II)

• Taking Care of Your Bowels: The Basics

• Taking Care of Your Bowels: Ensuring Success

Taking Care of Your Bowels - The Basics

[Download this pamphlet: "Taking Care of Your Bowels - The Basics" -978KB]

What is the bowel and what does it do?

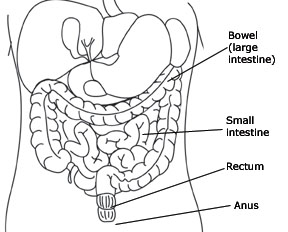

The bowel is the last portion of your digestive tract and is sometimes called the large intestine or colon. The digestive tract as a whole is a hollow tube that extends from the mouth to the anus (see illustration).

The function of the digestive system is to take food into the body and to get rid of waste. The bowel is where the waste products of eating are stored until they are emptied from the body in the form of a bowel movement (stool, feces).

A bowel movement happens when the rectum (last portion of the bowel) becomes full of stool and the muscle around the anus (anal sphincter) opens (see diagram below).

With a spinal cord injury, damage can occur to the nerves that allow a person to control bowel movements. If the spinal cord injury is above the T-12 level, the ability to feel when the rectum is full may be lost. The anal sphincter muscle remains tight, however, and bowel movements will occur on a reflex basis. This means that when the rectum is full, the defecation reflex will occur, emptying the bowel. This type of bowel problem is called an upper motor neuron or reflexic bowel. It can be managed by causing the defecation reflex to occur at a socially appropriate time and place.

A spinal cord injury below the T-12 level may damage the defecation reflex and relax the anal sphincter muscle. This is known as a lower motor neuron, flaccid or areflexic bowel. Management of this type of bowel problem may require more frequent attempts to empty the bowel and bearing down or manual removal of stool.

Both types of neurogenic bowel can be managed successfully to prevent unplanned bowel movements and other bowel problems such as constipation, diarrhea and impaction.

What methods can be used for emptying the bowel?

Each person's bowel program should be individualized to fit his/her own needs, type of nerve damage (upper or lower motor neuron) and other factors (see "What Factors can Affect the Success of the Bowel Program," below). Components of a bowel program can include any combination of the following:

- Manual Removal

Physical removal of the stool from the rectum. This can be combined with a bearing down technique called a valsalva maneuver (avoid this technique if you have a heart condition). - Digital Stimulation

Circular motion with the index finger in the rectum, which causes the anal sphincter to relax. - Suppository

Bysocodyl rectal suppository (Dulcolax® or Magic Bullet®) stimulates the nerve endings in the rectum, causing a contraction of the bowel. Glycerine draws water into the stool to stimulate evacuation. - Mini-enema (Enemeez®)

Softens, lubricates, and draws water into the stool to stimulate evacuation.

What is a bowel program?

Most people perform their bowel program at a time of day that fits in with their prior bowel habits and current lifestyle. The program usually begins with insertion of either a suppository or an Enemeez®, followed by a waiting period of approximately 5-10 minutes to allow the stimulant to work. This part of the program should, preferably, be done on the commode or toilet seat.

After the waiting period, digital stimulation is performed every 10-15 minutes until the rectum is empty. Persons with a flaccid (areflexic) bowel frequently omit the suppository or mini-enema and start their bowel program with digital stimulation or manual removal. Most bowel programs require 30-60 minutes to complete.

Bowel programs vary from person to person according to their individual preferences and needs. Some people use only half of a suppository, some require two suppositories, and some use no suppository or mini-enema at all. Some choose to do the entire program in bed, while others sit on the toilet from the beginning. Some find that the program works better if they can eat or drink a warm beverage while it is in progress, others find that this is not helpful. What is most important is that you discover what works best for you.

What factors can affect the success of the bowel program?

Any one of the factors listed below, or a combination of factors, can affect the success of a bowel program. Changing one factor may produce results almost immediately, or it may take several days to see the results. Changing more than one factor at a time makes it difficult to determine the effects of individual factors, and may increase the time it takes to develop a stable bowel program.

- Previous bowel history: What have your bowel habits been in the past?

- Timing: Do you do your bowel program in the morning or evening? At the same time every day? After a meal or warm beverage? What is the interval between programs -- half a day, one day or two days? (You should do a bowel program at least every 2-3 days to reduce your risk of constipation, impaction and colon cancer.)

- Privacy and Comfort: Does someone else share your bathroom? Do you have enough time to complete your program?

- Emotional stress: Has your appetite been affected? Are you able to relax?

- Positioning: Where do you do your program -- on a commode chair, raised toilet seat, on the toilet, or in bed? It will probably work better when you are sitting up because of gravity.

- Fluids: How much and what type of fluid do you drink? (Prune juice or orange juice can stimulate the bowels, or another type of fruit juice may work best for you.)

- Food: How much fiber or bulk (such as fruits and vegetables, bran, whole grain breads and cereals) do you eat? Some foods (such as dairy products, white potatoes, white bread and bananas) can contribute to constipation, while others (such as excess amounts of fruit, caffeine, or spicy foods) may soften the stool or cause diarrhea.

- Medication: Some medicines (such as codeine, Ditropan, probanthine, and aluminum-based antacids like Aludrox) can cause constipation, while others (including some antibiotics, such as ampicillin, and magnesium-based antacids such as Mylanta and Maalox) can cause diarrhea. Consult your health care provider for information about the medications you are taking.

- Illness: A case of the flu, a cold or an intestinal infection may affect your bowel program while you are ill. (Even if your digestive system is not directly affected, your eating habits, fluid intake or mobility may change, which can alter your bowel program.)

- Activity level/Mobility: How much exercise do you get? How much time do you spend out of bed?

- Weather: Hot weather increases the evaporation of body fluids, which can lead to dehydration and constipation.

- External massage: Massaging the lower abdomen in a circular, clockwise motion from right to left increases bowel activity.

- Valsalva: (bearing down)

This technique is not recommended for patients with cardiac problems. - Assistive/Adaptive Devices

Devices such as a suppository inserter, finger extension or digital stimulator may be required to assist you in establishing a successful bowel program.

University of Washington-operated SCI Clinics:

Harborview Medical Center

Rehabilitation Medicine Clinic

325 9th Ave., Seattle WA 98104

Spinal Cord Injury Clinic nurses: 206-744-5862

University of Washington Medical Center

Rehabilitation Medicine Clinic

1959 NE Pacific, Seattle WA 98195

Spinal Cord Injury Clinic nurses: 206-598-4295