SCI Forum

Pressure ulcers can wreck your life! Preventing and managing skin problems after SCI

Presented by Deborah Crane, MD, MPH and Beth Hall, RN, CWS on January 10, 2012 at the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, WA.

Presentation time: 50 minutes. After watching, please complete our two-minute survey!

You can also watch this video on YouTube with or without closed-captioning.

Click here to see all of our SCI Forum videos.

Report: Preventing and Managing Skin Problems after SCI

Contents

-

Part 1: Risks & Causes

-

Part 2: Prevention, Skin Monitoring and Wound Management

- How do you know you have a problem?

- Inspecting your skin

- Areas of the body most at risk

- What does it look like when a pressure ulcer is starting?

- What do you do if you suspect damage?

- Stages of pressure ulcers (with photos)

- Once a pressure ulcer has healed

- Principles of wound care

- Nutrition and pressure ulcers

- Don't forget!

-

Part 3. Surgical Interventions for Pressure Ulcers

-

References

-

More helpful resources on skin care and pressure sores

Part 1: Risks and Causes

By Deborah Crane, MD, MPH, Assistant Professor, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, UW Medicine

- What are pressure ulcers?

- How common are pressure ulcers?

- Why are we so concerned about pressure ulcers?

- Risk factors

- Causes

- Prevention

What are pressure ulcers?

The National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel defines a pressure ulcer as “a localized area of tissue necrosis that tends to develop when soft tissue is compressed between a bony prominence and an external surface for a prolonged period of time." More simply put, tissue death results when the soft tissue gets squeezed between a firm spot and something external to your body. The area of damage is the pressure ulcer or sore.

How common are pressure ulcers?

It is challenging to pinpoint the precise likelihood of developing pressure ulcers. About one-third of people with new spinal cord injuries develop pressure ulcers during their initial hospitalization.

A study that used the National Model Systems SCI database reported new pressure ulcers among 7.9% of persons in the first year after SCI and 8.9% in the second year. A study of 219 veterans reported only 19.6 percent had no history of pressure ulcers. Another study of 800 veterans found that 62.4% of participants experienced pressure ulcers within one to 52 years after SCI. According to the 1998 National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center (NSCISC) Annual Report, 2971 of 4065 persons with SCI (73%) developed pressure ulcers when studied over a 20 year period.

Why are we so concerned about pressure ulcers?

Pressure sores are a common cause of hospitalization

Once they go home after rehab, most folks with an SCI never want to be in a hospital again. But 39% of people rehospitalized in the first year after their SCI are admitted for pressure ulcers. And about one-third, or 34% of people with an SCI end up requiring three or more hospitalizations throughout the rest of their lifetime for treatment of pressure sores. If you want to stay out of the hospital, you definitely want to prevent a pressure sore.

Increased care needs—decreased independence

Having a pressure sore means you are likely to need more help with your personal care. You may go from being mostly or completely independent with your care to suddenly needing a lot of help and losing your independence if you get a pressure ulcer.

Expense

About 25% of the total lifetime cost of medical care for a person with SCI is related to pressure sores. Unfortunately, SCI is an expensive situation to be in, and we all want to reduce that cost as much as possible.

Personal costs

Perhaps most important of all, pressure sores can really change your life and have multiple negative consequences, including loss of income because you’re on bed rest and can’t go to work; increased care costs; the negative health effects of prolonged bed rest and inactivity; and loss of your usual activities and sources of life satisfaction. There’s a lot of personal suffering with dealing with a chronic sore, and it certainly can contribute to depression.

Death

About 7–8% of deaths in the SCI population are related to a pressure sore. These deaths most likely result from sepsis, an infection that spreads throughout the body in the blood and tissues.

Risk factors

There are several factors that put a person with SCI at risk for pressure ulcers. Some are a direct consequence of the SCI, and some are not.

SCI-related risk factors

- Paralysis and sensory impairment (if you are unable to feel things normally, you won’t know if something is irritating your skin).

- Changes in collagen metabolism (the way your skin and connective tissues are able to build new tissue and heal) caused by SCI. Wound healing may take five times longer below the level of SCI due to these changes.

- Muscle atrophy (shrinking) can leave the bony prominences on your backside (or other areas) less padded, so that there is less protection over these areas.

- Altered circulation can reduce the blood supply to tissues, which not only increases your risk for skin problems, but slows the healing process if you do develop a pressure sore.

Other risk factors not related to your SCI

- Hypogonadism (low testosterone), which is more common in men with SCI than those without, can inhibit or slow wound healing. It’s important to get your testosterone level checked at least every couple of years. Ask your provider to do this if he or she isn’t aware that this is a problem for people with SCI.

- Diabetes.

- Fevers or illnesses.

- Malnutrition. Protein stores, vitamin C levels, and zinc levels, are particularly important in healing wounds and maintaining healthy skin.

- Smoking contributes to peripheral vascular disease, which makes it more difficult to heal a wound and more likely to develop a wound.

- Aging, which we unfortunately can't escape, often increases your risk.

- Skin gets thinner as one ages and tends to be less tolerant to trauma and shearing (dragging or rubbing) forces.

- People tend to lose some strength as they age, so transfers that were going really great when you were 25 might not be going as well when you're 75. When you aren’t as strong, you might be more likely to drag your bottom across a surface and injure your skin.

Causes

Pressure

This is the most common cause, and it’s important to be aware of how different amounts and duration of pressure can cause damage to skin. All of these conditions can be damaging:

- Long periods of low pressure — it is estimated that between one and six hours of constant low pressure can cause some tissue damage. While sitting is relatively low pressure, forgetting to do pressure reliefs all day makes the pressure constant and can cause damage.

- Recurrent pressure, such as frequently bumping your elbow against a table, desk, or arm rest many times each day.

- Short periods of high pressure, such as accidently whacking yourself hard against a surface when doing a transfer.

Body tissues vary in their tolerance or their sensitivity to pressure. Skin is actually the most pressure-resistant compared to other body tissues. Muscle, because it is so metabolically active, can start to have problems more quickly than other tissues. That is why it’s possible for muscle underlying the skin to be damaged while the skin above it is still intact.

Shear

Dragging skin or body parts across a surface, as when transferring without lifting your backside off the surface, can damage your skin.

Positioning

Abnormal or less than ideal positioning in your wheelchair, vehicle, or other equipment can increase pressure over specific bony areas.

Skin moisture and maceration

Skin that is exposed to moisture for extended periods can become macerated (softened and weakened) and vulnerable to breakdown. We worry most about exposure to urine and feces due to incontinence, but sweat can also be a problem.

Prevention

Pressure

- Inspect your skin carefully twice daily (learn more ).

- Perform pressure reliefs every 15 to 30 minutes. (Learn how to do pressure reliefs properly at http://sci.washington.edu/info/pamphlets/msktc-pressure_relief.asp.)

- Turn frequently in bed. The usual recommendation is to turn every two hours in bed, but this can sometimes be stretched out to longer periods (usually up to four hours) eventually.

- Use wheelchair cushions and mattresses that distribute pressure well and are inflated and maintained correctly.

Shear

- Keep clothing and linens wrinkle-free.

- Maintain good transfer technique — make sure you aren’t dragging your lower limbs or back side across a surface when transferring.

- Protect hands, legs, feet and arms from trauma.

Positioning

- Make sure your positioning, posture and seating are correct. Consult your health provider or a seating specialist if you aren’t sure.

Moisture

- Maintain clean, dry skin.

- Maintain bowel and bladder continence.

Mental status

- Many medications commonly prescribed for individuals with SCI can cause sedation (sleepiness) or even confusion. Talk to your health provider about managing your medications so these kinds of side effects do not keep you from maintaining good skin care.

Alcohol and recreational drugs

- Alcohol or other drugs used for recreation or abuse can reduce your alertness, judgment, and attention to doing pressure reliefs and good transfers.

Smoking

- There are lots of reasons not to smoke. Skin health is definitely one of them.

Low testosterone

- Men should have their testosterone checked every few years.

Anemia and nutrition

- Make sure you're eating a diet that's high in protein, iron, and vitamin C. (Learn about nutritional guidelines for persons with SCI at http://sci.washington.edu/info/forums/reports/nutrition_2011.asp.)

- Make sure your provider is watching your different vitamin levels.

Part 2: Prevention, Skin Monitoring and Wound Management

By Beth Hall, RN, CWS, Wound Nurse Specialist, Harborview Medical Center

This part of the presentation is on prevention and management—what to look for, what to do, and what are the signs of early skin damage.

- How do you know you have a problem?

- Inspecting your skin

- Areas of the body most at risk

- What does it look like when a pressure ulcer is starting?

- What do you do if you suspect damage?

- Stages of pressure ulcers

- Once a pressure ulcer has healed

- Principles of wound care

- Nutrition and pressure ulcers

- Don't forget!

How do you know you have a problem?

- You have to know your skin.

- That means you need to look and feel.

- You need to establish a routine where you're checking your skin in the mornings before you get dressed and at night when you go to bed.

Inspecting your skin

- Use a mirror if you're able to.

- Designate a caregiver if you're not able to use the mirror.

- Either way, know what your skin looks like, because your caregiver might change, but your skin will always be with you.

- Take photos, save them, send them to your health provider if necessary. Make use of technology like iPad, iPhone and cameras.

- If you suspect skin breakdown, always use some kind of measuring device. Record its size so you can track its development or healing and can report the information to your health provider.

Areas of the body most at risk

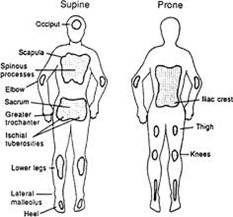

Any areas with bony prominences are vulnerable to pressure sores, such as heels, knees, elbows, ischial tuberosities (sitting bones), sacrum (tail bone), iliac crest (lower back), shoulder blades, and the back of the head.

Figure 1. Areas at risk.

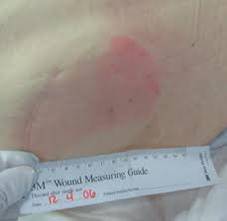

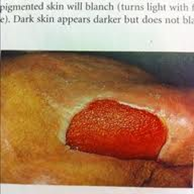

What does it look like when a pressure ulcer is starting?

In pale or light complexions, look for skin that is:

- Reddish or pinkish.

- Shiny.

- Has texture changes—cracked, dry, hard, soft, warm, or with some swelling at the site.

- Looks like a bruise.

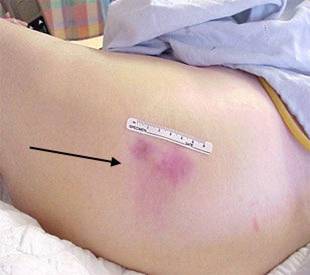

In dark complexions, look for skin that is:

- Darker than the surrounding skin.

- Shiny, bluish or purplish.

- Has texture changes—cracked, dry, hard, soft, warm, or with some swelling at the site.

- Blistered—you might not be able to see it, but you can probably feel it.

Figure 2. Early skin damage, pale complexion.

Figure 3. Early skin damage, dark complexion.

What do you do if you suspect damage?

- The first thing you do is remove the pressure immediately.

- Perform a blanching test (for light skin complexion only): Press on the discolored area with your finger; the skin should turn white. Remove your finger; the color should return in a few seconds. if it doesn't, then you know the blood flow has been interrupted and skin damage has begun.

- Recheck it after 10–30 minutes. If the area is still discolored, you should assume that a pressure ulcer hast started.

- Look for the source of pressure.

- Check your mattress—is it providing enough pressure redistribution?

- Check your wheelchair cushion—is it inflated? Is it the right kind of cushion? Is there a leak?

- Check your clothes for wrinkles, big seams or pockets.

- Were there objects left in the bed that you might have lain on or sat on in the wheelchair?

- Evaluate your posture in your wheelchair.

- Check your positioning in bed—are you making sure that all your bony prominences are padded?

If you don't correct the problem at the source, you might clear up one pressure ulcer, but it's just going to happen again.

Remember!

- What you see on the surface is often the smallest part of the pressure ulcer.

- Every area of pressure on the skin, no matter how small, needs to be regarded as a serious problem because of the potential damage to the tissue you can't see.

- Don't be fooled into thinking you only have a little problem. All changes in your skin are potentially serious.

Stages of pressure ulcers

These official staging definitions come from the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (http://www.npuap.org/) .

Stage I

- Outer layer of skin (epidermis) is damaged but not broken.

- Appears as a change in color. In pale complexions, the site may be red or pink. In dark complexions, it is darker than the surrounding skin.

- The discoloration will not fade or blanche.

Figure 4. Stage 1 pressure ulcer, dark complexion.

Figure 5. Stage 1 pressure ulcer, pale complexion.

Figure 6. Stage 1 pressure ulcer, pale complexion.

Treatment

- Keep all pressure off the area.

- Find and remove the pressure.

- On the ischium (sitting bones), stay out of your wheelchair.

- On the sacrum ( tailbone) or shoulder blades, stay off your back in bed; check the back of your wheelchair; and check seams, wrinkles and pockets on your clothes.

- On the heels, ankles and feet, float them off a surface, hang them off the end of a bed or use splints.

- Keep the area clean and dry, and do not rub it.

- Eat enough calories, including Protein, Vitamins A and C, Iron and Zinc.

- Increase your water intake.

- Check the site at least twice a day.

- Review your transfer and pressure relief techniques and check your equipment.

- If the reddened area seems to be caused by friction and you just can't stop it, try a transparent dressing to help the skin slide over a surface.

Usual healing time

If you follow the appropriate treatment, a Stage I pressure ulcer can be resolved in about three days. If you follow the treatments and still can't heal it, contact your healthcare provider. Early detection and appropriate treatment can prevent future problems.

Stage II

- There is a break in the skin.

- It is considered a partial-thickness injury. Stage I was just on the surface, the epidermis. Stage 2 is through the epidermis into the dermis (layer of tissue under the skin).

- It presents like a shallow, open wound.

- The tissue looks red.

- It may or may not have drainage.

- It may be dry or moist.

Figure 7. Stage 2 pressure ulcer, dark complexion.

Figure 8. Stage 2 pressure ulcer, dark complexion.

Figure 9. Stage 2 pressure ulcer, pale complexion.

Treatment

- Keep all pressure off.

- Follow recommendations for Stage I.

- Keep the ulcer clean and the surrounding skin dry.

- Contact your health care provider for wound care recommendations and dressing choice.

- Look for signs of healing, signs of getting worse, or signs of infection.

- Monitor the wound closely, take pictures, and measure weekly.

Usual healing time: three days to three weeks.

Signs the wound is healing

- The ulcer gets smaller, shallower, and some pinkish tissue starts to form around the edges.

- It starts to close up.

- The wound surface may be smooth or bumpy.

- It is beefy red, and you may have some bleeding, but that's good because it shows you've got good circulation.

Figure 10. Signs the stage 2 pressure ulcer is healing.

Figure 11. Signs the stage 2 pressure ulcer is healing.

Figure 12. Signs the stage 2 pressure ulcer is healing.

Signs the wound is getting worse

- The ulcer increases in size, depth and/or drainage.

- Dead, black tissue may be present.

- The wound might start smelling.

- Drainage might be greenish.

- You might develop a fever.

- You need to call your provider.

Figure 13. Signs the wound is getting worse.

Figure 14. Signs the wound is getting worse.

Figure 15. Signs the wound is getting worse.

Stage III

- The wound goes through the epidermis and dermis and into the subcutaneous (fatty) tissue. This is considered a full thickness injury.

- Presents as a deeper crater.

- Appears red.

- May have necrotic (dead) tissue on it, which can be white, yellow, gray, black.

- Dead tissue needs to be removed before healing can occur.

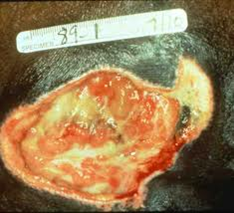

Figure 16. Stage 3 pressure ulcer - pale complexion.

Figure 17. Stage 3 pressure ulcer - pale complexion.

Figure 18. Stage 3 pressure ulcer - dark complexion.

Treatment

- Keep all pressure off.

- Notify your health care provider.

- Maintain good hygiene and dry skin.

- Evaluate your diet, increase protein, Vitamins A&C, Zinc, and Iron.

- Usually requires packing, a debriding agent, or antibiotic in addition to outer dressing.

- Measure weekly and take photos; share them with your provider.

- You will need home health care and prolonged bed rest.

- You may qualify for a special bed or mattress.

Usual healing time: one to four months.

Signs the wound is getting worse

- More dead tissue.

- Wound is starting to extend into the surrounding tissue, undermining and possible tunneling.

Figure 19. Signs the stage 3 pressure ulcer is getting worse.

Signs the wound is healing

- Decrease in dead tissue.

- The cavity starts to fill in.

- Pinkish tissue around the edges.

Figure 20. Signs the stage 3 pressure ulcer is healing.

Figure 21. Signs the stage 3 pressure ulcer is healing.

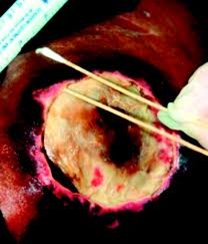

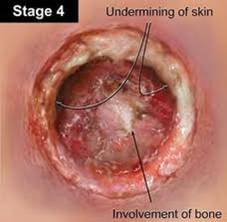

Stage IV

- This is a full thickness wound and extends into the muscle and can lead to the bone, the tendon or the joint capsule.

- It's a large cavity wound with undermining and tunneling.

- Dead tissue is often present.

- Usually lots of drainage.

- Infections are common.

Figure 22. Stage 4 pressure ulcer - dark complexion.

Figure 23. Stage 4 pressure ulcer - pale complexion.

Treatment

- Keep all pressure off.

- Follow all the same steps as the other stages.

- Requires more frequent contact with your health care provider and home health visits.

- Will require a special mattress.

- Requires rolonged best rest, possibly even placement in a skilled nursing facility.

- Surgery is often required to debride or close the wound.

Usual healing time: three months to two years.

Signs the wound is healing

As with Stage III, the wound starts to fill in, and tissue becomes pink.

Figure 24. Signs the stage 4 pressure ulcer is healing.

Figure 25. Signs the stage 4 pressure ulcer is healing.

Figure 26. Signs the stage 4 pressure ulcer is healing.

Signs the wound is getting worse

It spreads into the surrounding tissue. There are signs of infection and probably evidence of bone or tendon damage.

Figure 27. Signs the stage 4 pressure ulcer is getting worse.

Unstageable pressure ulcer

It can't be staged, because if you can't see the base of a wound, you can't determine the extent of the damage.

- Wound is covered with necrotic tissue, which may be tan, gray, green or brown.

- May also present with a thick, dry scab or eschar that can be tan, brown, or black.

- You cannot see the base of wound.

Figure 28. Unstageable pressure ulcer.

Figure 29. Unstageable pressure ulcer.

Treatment

- Keep the pressure off.

- Notify your health care provider.

- Dead tissue must be debrided (removed) before the ulcer can be staged and healing can begin.

- Cover with clean, dry, dressing until you're seen by a healthcare provider.

- If a cavity is present, gently fill it with absorptive gauze until you’re seen by a health care provider.

Usual healing time: You cannot determine a healing time until the extent of the damage is known.

Suspected deep tissue injury

- Skin is intact but looks bruised.

- Damage is to underlying soft tissue, where the tissue meets the bone.

- The wound has not yet reached the surface of the skin, but these often develop into a Stage III or IV pressure ulcer.

- Bruise can be soft, mushy, warm or cool.

- In a dark complexion, it may present as a thin blister over a dark wound bed.

- Wound may evolve and become covered with thin scab.

- It can be caused by friction or shearing. It is fairly common on the feet.

Figure 30. Suspected deep tissue injury.

Figure 31. Suspected deep tissue injury.

Figure 32.Suspected deep tissue injury.

Figure 33. Suspected deep tissue injury.

Treatment

- Keep the pressure off.

- Check your equipment. Check your shoes. Are they slipping on your feet? Are they too tight?

- Notify your health care provider.

- If you do have a blister, cover it with a clean dressing until you're seen by your healthcare provider.

Usual healing time: You cannot determine a healing time until the extent of the damage is known.

Once a pressure ulcer has healed

- You need to increase your sitting time gradually, about 15 minutes at a time, and always check your skin after that.

- The strength of the healed tissue is only 80% of what it was prior to injury, so it is more at risk for another pressure ulcer.

Principles of wound care

1. Eliminate pressure.

- This may mean prolonged bed rest. Unfortunately, the treatments required to successfully heal pressure ulcers can cause a serious disruption of your life. Prolonged bed rest can result in resultant respiratory, urinary tract, and psychological complications. The inability to work or maintain your job can cause financial hardships. The inability to participate in social or recreational activities can lower your quality of life and cause depression.

2. Local wound care.

- The standard of care is moist wound healing.

- Removal of necrotic tissue through some form of debridement. Types of debridement:

- Topical treatment can be used, like an enzyme, to break down dead tissue, along with an antibiotic ointment if there are signs of local infection.

- If it's draining a lot, your healthcare provider may recommend a filler. This can be a paste, powder, or beads, or an alginate that absorbs a lot of drainage, which cuts down on the number of times you have to do wound care.

- Other -- medihoney, silver, growth hormones, other the topical treatments ordered by your healthcare provider.

- Keep wound clean and surrounding skin intact.

- Use topical treatment if ordered by health care provider.

3. Monitor and measure

- Look and feel.

- Take photos.

- Use a measuring device when you're taking the photo.

Figure 34. Wound care: Measure and monitor.

- Keep in contact with your healthcare provider and share your photos.

- Dressing choice depends on amount of drainage, size and stage of ulcer, and frequency of would care.

- There are many types and manufacturers of dressings, but only a few major categories:

- Foams

- Gauze

- Hydrocolloids—absorb moisture.

- Hydrogels—retain moisture, if the wound is dry.

- Transparent film dressing

Nutrition and pressure ulcers

- Develop good eating habits. Poor nutrition prevents the body tissue from rebuilding, staying healthy, or fighting infection. You need to eat a balanced diet with adequate protein, fruits, vegetables, grains and fats.

- If you question your nutritional status or need help improving your nutrition, talk with your health care provider.

- If you have a pressure ulcer, your protein requirements are at least double the normal amounts. For example, the average (150 lb.) adult needs .6 to .8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day. This amounts to about 1 ½ chicken breasts and a 7-ounce steak per day. If you have a Stage II pressure ulcer, that doubles (to 1.2–1.5 gram/kg body weight/day). It almost triples (1.5–2.0 grams) if you have a Stage III or IV ulcer. That is a lot of food! Supplements like Ensure can help.

- Learn more from the SCI Forum on Nutrition and Spinal Cord Injury.

Don't forget!

- Pressure ulcers are preventable.

- Monitor your skin. That way you should be able to detect a change in the early stages and treat it accordingly.

- Aging increases the chance of developing a pressure ulcer because skin gradually changes and loses elasticity and strength as we age.

- At the first sign of skin damage, get the pressure off.

- Look at your pressure relief techniques and check your equipment. If you develop a pressure ulcer and you treat it appropriately, you can probably heal it. But if you don't find the cause of it and rectify that, it's just going to happen again.

- Don't hesitate to ask for ongoing help from your healthcare provider. These are complicated problems, and I don't think anybody expects you to do this by yourself.

Part 3. Surgical interventions for pressure ulcers

By Deborah Crane, MD, MPH, Assistant Professor, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, UW Medicine

Because of complications, failure rates, and other considerations, surgery is the option of last resort for treating pressure ulcers. It is not an easy or quick fix, and we hope that you never need to have this kind of surgery.

When is surgery considered?

Your physician or provider may start to think about getting a plastic surgeon to evaluate your ulcer in these situations:

- Stage III and IV ulcers, particularly when bones or joints are involved.

- Ulcers with sinus tracts—tunnel-like areas where your provider or nurse can probe with a small object such as a Q-tip .

- Ulcers that have significant undermining – cave-like wounds where the opening is smaller than the interior of the wound.

- Chronic ulcers that become “stalled” and don’t progress to healing in spite of good care.

What kind of surgery is available?

- Flap surgery uses a “flap” of the patient’s own muscle tissue to fill the wound so it can heal. It is typically performed by a plastic surgeon. The surgery involves cutting out the ulcer and any surrounding scar or underlying dead tissue or bone. The empty space is most often filled with a flap of nearby muscle, which helps cushion bony areas and maintain blood flow to the area. Operating time takes about three hours.

Surgery complications and failures

- Complications: research studies show that complications are common following flap surgeries to treat pressure ulcers. A study led by a group of plastic surgeons at the Seattle VA found that only 27% of cases healed without any complications. Complications ranged from minor setbacks, such as a small infection, to major failure in which the patient had to go back through the entire surgery again.

- Same-site recurrences: studies vary widely, but between 19–64% of patients who have had flap surgery end up developing another pressure ulcer in the same location where the flap surgery was done.

- New ulcers: about 22–31% of patients who have had flap surgery for a pressure ulcer go on to develop a new ulcer in a different area.

Who is the right candidate for flap surgery?

While many studies have examined this question, there has been little agreement on which factors—such as a patient’s age—predict whether flap surgery will be successful or not. All agree that smoking predicts a poor outcome or complication. In fact, smoking is so universally recognized as contributing to a bad outcome that many surgeons will not consider doing the surgery if the patient is still smoking.

What happens after surgery?

- You are often hospitalized for six weeks (or more) after a flap surgery.

- You receive IV antibiotics, which often continue for several days to weeks.

- Surgical drains remain in place for days to weeks, depending on how much drainage you have.

- You are kept on bed rest (and cannot get up to your wheelchair) in an air-fluidized bed for 2–4 weeks.

- If healing is progressing well, you are switched to a low-air-loss mattress 2-3 weeks after surgery.

- You then begin range of motion and stretching exercises with physical and occupational therapists (PT and OT).

- You are advanced to a gradual sitting program in your wheelchair.

- You are discharged from the hospital once you are sitting at least four hours at a time and your skin is holding up.

This entire process usually takes place either in the hospital or a nursing facility. If all goes well, after about six weeks you will be able to go home and gradually return to some of your normal activities.

References

-

Montroy RE, Eltorai I. The surgical management of pressure ulcers. In Lin VW, Cardenas DD, Cutter NC, et al. Spinal Cord Medicine: Principles and Practice. New York, NY: Demos Medical Publishing, Inc; 2003:591-610.

-

Pressure Ulcer Prevention and Treatment Following Spinal Cord Injury: A Clinical Practice Guideline for Health-Care Professionals. Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine Clinical Practice Guidelines. Paralyzed Veterans of America; 2000:1-62.

-

Priebe MM, Martin M, Wuermser LA, Castillo T, McFarlin J. The medical management of pressure ulcers. In Lin VW, Cardenas DD, Cutter NC, et al. Spinal Cord Medicine: Principles and Practice. New York, NY: Demos Medical Publishing, Inc; 2003:567-87.