SCI Forum Report

Getting Your Zzz's:

Sleep Problems and Sleep Apnea in Persons with Spinal Cord Injury

Presented by Don Fogelberg, PhD, and Stephen Burns, MD on February 12, 2012 at the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, WA.

Presentation time: 80 minutes. Part 1 (sleep problems) runs for the first 19 minutes 20 seconds, followed by Part 2 (sleep apnea) for the remainder of the video.

After watching, please complete our two-minute survey!

You can also watch this video on YouTube with or without closed captioning.

For a complete list of our SCI Forum videos, go to http://sci.washington.edu/info/forums/forum_videos.asp.

Report: Sleep Problems and Sleep Apnea in Persons with Spinal Cord Injury

Contents

-

Part 1: Sleep Problems in Persons with Spinal Cord Injury

-

Part 2: Sleep Apnea and Spinal Cord Injury

Part 1: Sleep Problems in Persons with Spinal Cord Injury

By Don Fogelberg, PhD, Assistant Professor of Occupational Therapy in the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Washington.

Why is sleep important?

Sleep is essential for health, and not getting enough sleep can have serious negative effects on your health and your cognitive (thinking) function.

Cognitive problems:

- Decreased alertness

- Problems remembering

- Shorter attention span

- Impaired judgment and decision-making. This is one reason why sleep loss is a risk for automobile crashes and industrial accidents.

Health problems:

- Increased pain. The relationship between sleep loss and pain is complex. If you're in pain, you're probably not going to sleep as well. It’s going to be harder to both fall asleep and stay asleep. But studies also show that if you don't get enough sleep, you become more sensitive to pain. So, your experience of pain actually increases. And this can create a kind of vicious downward spiral. The more pain you have, the harder it is to get sleep; the harder it is to get to sleep, the more pain you have.

- Increased depression. Sleep disturbances are often thought of as symptom of depression and low mood. But studies have found that depression is often preceded by a long period of sleep problems.

- Interference with immune function and endocrine system function.

- Obesity. There are number of metabolic changes that happened when you are sleep-deprived that make you gain weight more easily.

- Diabetes.

- Cardiovascular disease (CVD).

The fact that obesity, diabetes and CVD are among the top causes of death in the U.S. highlights the critical importance of sleep.

Types of sleep problems

There are dozens of recognized sleep disturbances, but three major types are most relevant to SCI: circadian rhythm sleep disorders, insomnia, and sleep-related breathing disorders (sleep apnea).

Circadian rhythm sleeps disorders (CRSDs)

These disorders occur when our internal body clock that governs our sleep-wake cycle gets out of alignment with the normal 24-hour day. Our internal clocks normally run on a slightly more than 24-hour cycle, but are constantly reset by visual cues of light and dark, as well our meal and exercise schedules.

Treating CRSDs usually involves resetting the internal clock by means such as light exposure, physical activity, or taking melatonin, a hormone that helps regulate sleep. There are six major types of circadian rhythm sleep disorders, and all of them result in excessive sleepiness and lack of daytime alertness.

- External causes:

- Jet lag, due to flying to a new time zone when your body clock is set in the old one.

- Shift work disorder occurs when a person is working during the normal sleep time (graveyard shift, early morning shift, rotating shift).

- Internal types. These can be very resistance to behavior change:

- Advanced sleep phase disorder: you tend to fall asleep and wake up too early.

- Delayed sleep phase disorder: you tend to stay up later and want to wake up later than the normal clock.

- Irregular sleep-wake rhythm: there’s no set pattern; sleep is fragmented into a series of naps.

- Free-running: a variable sleep cycle that shifts later every day.

Insomnia

Insomnia is defined as difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep or both, resulting in insufficient or poor quality sleep and daytime sleepiness. This can be an acute, isolated case lasting only a couple of nights, or a nightly problem that continues for years. Insomnia is very common, affecting approximately 33% of the U.S. population. It is considered to be one of the most common psychological problems in the US today.

Secondary Insomnia

Insomnia is often considered to be “secondary” because it so often occurs along with other medical conditions. Many medical problems could lead to difficulty getting enough sleep, including pain, physical or neurological disorders like arthritis, chronic bladder infection and Alzheimer's disease. Psychological disorders—depression, anxiety, panic attacks—are also associated with poor sleep.

It is also possible to have an insomnia problem caused by a treatment for another disorder. For example, inhalers for asthma can actually have a stimulant effect and keep you from sleeping well. And insomnia may be a result of another sleep disturbance like a circadian rhythm disorder. The idea with secondary insomnia is that if you treat the secondary condition, the insomnia will go away on its own. But that isn’t always the case.

Primary insomnia

An emerging consensus among sleep researchers is that insomnia really needs to be thought of as a disorder in its own right and treated as such. We know that the symptoms and consequences of insomnia are relatively consistent regardless of what disorder it's associated with. Meanwhile, the course of insomnia is often different from that of the associated disorder—your arthritis or the pain might get better, but the insomnia can continue or even get worse. And the same treatments are effective for insomnia regardless of what else is going on. In some cases, treating the insomnia by itself may make it easier to treat depression, pain, or other co-occurring conditions.

So, sleep researchers are now saying that we need to look again at insomnia and not just assume that it's something that will clear up whenever the associated condition clears up.

Why is sleep affected by SCI?

Several conditions common to SCI may make sleep more difficult for this population:

- Melatonin, the hormone that regulates the sleep-wake cycle, is often reduced in persons with high-level SCI. If you're not making enough melatonin, it may be more difficult for your internal clock to reset.

- Antidiuretic hormone (ADH) normally increases at night, suppressing urinary output. But in people with SCI, ADH levels often don’t increase at night, so urinary output remains at daytime levels. If you need to go to the bathroom more at night, your sleep gets interrupted.

- SCI can disrupt the body’s temperature regulation system, and since the internal thermostat determines timing of sleep onset, you may not be sleepy at the normal bed time.

- Pressure ulcer prevention routines, such as having to awaken to turn and move around at night.

- Changes in activity levels. Not being as active means you might not be as sleepy.

- More time spent in bed.

Tips for improving sleep (sleep “hygiene”)

Guidelines from the American Sleep Association:

- Maintain a regular sleep schedule—this will help in resetting your internal clock.

- Develop a comfortable pre-sleep routine to help calm your nervous system down before sleep.

- Avoid naps if possible so you’re more likely to be sleepy at bedtime.

- Watch your intake of caffeine and other stimulants, especially in the afternoon.

- Hide or don’t look at your clock. Being too aware of how late it’s getting just makes you more anxious as the night goes on.

- Don’t stay in bed awake and trying to fall asleep for more than 10 minutes. Get out of bed and do some non-stimulating reading, or simply sit in the dark for a while. However, if getting in and out of bed is a production, as it might be for someone with SCI, this rule may be difficult to follow.

- Don’t watch TV or read in bed. The American Sleep Association likes to say that the bed is for sleep and hanky-panky, and that’s all.

Part 2: Sleep Apnea and Spinal Cord Injury

By Stephen Burns, MD, Associate Professor and physiatrist in the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine at the University of Washington and Director of the SCI Service at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System in Seattle.

- Sleep disturbances and alertness

- Sleep apnea and sleep disordered breathing

- Treatments for sleep apnea

- Avenues for future research

Sleep disturbances and alertness

Sleep disturbances can be a minor inconvenience with a small effect on quality of life, or it can be a big problem that overwhelms a person’s whole life.

To be refreshed and alert in the daytime, we need enough hours of sleep and minimal interruption so we can go into the deep phases of sleep that are most restful, including the dream—or REM—phase. When we sleep well, we can be alert during the daytime, have enough energy to participate in activities, not fall asleep as we're driving our cars, and stay alert until bedtime, at which point we start to wind down and fall into some nice restful sleep. That’s the ideal.

There are many barriers to getting good, restful sleep after SCI:

- Needing to awaken a number of times during the night for care, such as doing intermittent catheterization in the middle of the night or turning yourself in bed to protect your skin.

- Pain that interferes with falling asleep and staying sleep.

- Spasticity.

- Lack of physical activity.

- Depression can interfere with your ability to fall asleep and stay asleep for the full night.

Poor sleep causes daytime sleepiness, which in people with SCI can be confounded by medications prescribed for pain, spasticity and neurogenic bladder that also cause sleepiness.

Sleep medicine is a relatively new field usually practiced as a subspecialty of pulmonary medicine, neurology/psychiatry, and otolaryngology, although some internists and pediatricians also subspecialize in sleep medicine. We are learning more about sleep all the time, and it is only a relatively recent discovery that sleep-disordered breathing is so common in people with neuromuscular disorders like SCI.

Sleep apnea and sleep-disordered breathing

There are three types of sleep-disordered breathing. Two of them are “apneas”—meaning pauses in air movement during sleep. Obstructive sleep apnea, the most common type, is discussed at length below. Central sleep apnea is a rare form of the disorder, in which the brain “forgets” to breathe. Hypoventilation (known as “chronic alveolar hypoventilation”), also rare, is very slow or shallow breathing rather than pauses in breathing.

What is sleep apnea?

Sleep apnea is defined as having numerous episodes during the night when breathing stops for at least 10 seconds. No air is moving in or out, and this causes a drop in the oxygen level in the body. In obstructive sleep apnea, breathing stops because the soft palate and tongue have flopped back and blocked (“obstructed”) the airway. It is worse when people sleep on their backs because gravity allows the tongue—which is a big muscle—to flop back into the throat. Snoring is usually severe, due to vibrations from air trying to push through the floppy tissues. When the airway is obstructed, the oxygen level drops. The brain senses this and wakes up just enough to take a deeper breath, open up those airway muscles and let some air pass through. More frequent and severe apnea tends to happen in the deepest phases of sleep, which are the phases you need in order to be well-rested.

Obstructive sleep apnea—referred to here as simply “sleep apnea”—is the most important medical cause for poor sleep quality and excessive daytime sleepiness in people with SCI. Sleep apnea can lead to serious health problems such as heart and lung disease. Fortunately, there are treatments available that can dramatically improve symptoms and avoid the negative health consequences.

In the general population, sleep apnea occurs in about three to four percent of males and one to two percent of females. Obesity is the main risk factor in this population, primarily from excess fat compressing the airway. Abdominal fat is a contributing factor because the diaphragm has a harder time pushing against it.

In the general population we know that sleep apnea has several serious consequences:

- Excessive daytime sleepiness

- Cognitive dysfunction, including both a short term drop and a permanent decline in cognitive abilities.

- Cardiac and pulmonary diseases, including hypertension (high blood pressure) that is resistant to several medications.

- Greatly increased risk for motor vehicle crashes.

How is sleep apnea diagnosed?

Oximeter or pulse ox

Sleep apnea reduces the amount of oxygen coming into the body and the amount of carbon dioxide going out of the body. An oximeter—also known as pulse ox because it also measures heart rate—is a simple fingertip sensor that measures the amount of oxygen in the blood. The reading shows the percent saturation of oxygen in red blood cells, which should be in the 90s. If it's below 90, something is wrong.

Figure 1. Pulse oximeter.

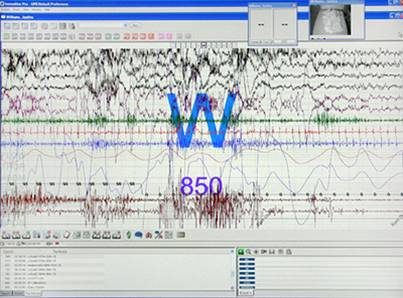

Polysomnography (PSG)

The Cadillac or “gold standard” of sleep studies is the polysomnogram or polysomnography (PSG). Poly means multiple; somno means sleep, and graphy/gram means graph or written record. The PSG measures many things, including:

- Breathing effort (measurement belts around trunk measures whether the chest is moving as air goes in and out).

- Airflow through mouth and nose.

- Eye movement and brain waves (for sleep staging).

- Body position and body movement using video. This can show limb movement disorders.

- Noise from snoring.

- Oxygen level.

- Heart rate and arterial tone.

PSG studies take place in a sleep lab. The patient is wired up to various machines and told to fall asleep as usual. Measurements are taken all night long and recorded on a printout called a polysomnograph.

Figure 2. Wired up in a sleep lab.

Figure 3. Polysomnograph report.

PSG results can tell us:

- The number of apnea events per hour. More than 15 events per hour is considered a significant problem.

- Oxygen desaturation, including the percent of time within different saturation rates and the lowest recorded saturation.

- Total sleep time and the amount of time spent in different sleep phases.

Other studies

- Limited sleep studies, limited channel studies, or cardiorespiratory studies are less expensive and easier to do. They measure oxygen level, heart rate, chest movement and air flow throughout the night but do not record information about sleep phases.

- Watch-PAT measures peripheral arterial tone (PAT) and pulse ox in a wrist-mounted device The PAT rises with apnea episodes. PAT is controlled by the sympathetic nervous system, however, and since this is altered in people with SCI, we can’t be sure how reliable the PAT test is for the SCI population.

How common is sleep apnea in the SCI population?

Only a few research studies have been done in this area.

Acute SCI

- Studies in Australia found that between 60 and 80 percent of people with new tetraplegia had sleep apnea.

- A pilot study at Harborview Medical Center to test for sleep apnea in the first six weeks after injury was inconclusive because it was so difficult to test people in the first few weeks, especially those at highest risk who were still on ventilators or medically unstable.

Chronic SCI

- Depending on the population being studied (different levels/severities of injury), type of test and cutoff scores, estimates in the chronic population range from 35 to 60 percent.

Why is sleep-disordered breathing so common after SCI?

There are numerous potential reasons for such a high rate of sleep apnea in SCI, including:

- Obesity, although many non-obese individuals with SCI also have sleep apnea.

- Weakness of breathing muscles.

- Altered breathing mechanics (inward collapse of the ribcage when the diaphragm contracts to try and take in a breath).

- Sleep apnea is more common in males, and most people with SCI are male.

- Medications that affect respiration. For example, baclofen relaxes airway muscles, promoting collapse.

- Many people with SCI can only sleep on their backs.

Negative consequences specific to SCI

People with SCI experience the same negative consequences from sleep apnea as anyone else, plus there could be some serious problems specific to SCI:

- In acute rehab, problems learning and participating fully in therapies due to sleepiness, which can result in poor adjustment and less independence when leaving rehab.

- Difficulty maintaining overall health because sleepiness makes you less attentive to personal care needs and safety.

- Poor wound healing or pressure ulcer formation due to low oxygen at night or not doing pressure reliefs because you keep falling asleep in your wheelchair.

- Difficulty adjusting psychologically to your disability.

- Sudden death. There are many unexplained deaths in the first year after injury. The autopsy shows nothing, and we say it was probably something heart related; but it’s very possible that it was something brought on by a bad apnea and low oxygen levels.

Barriers to diagnosing sleep apnea in SCI

- Hospital staff don’t always suspect sleep apnea. Sleepiness is common among inpatients for many other reasons, such as the medications they are on.

- If patients are not obese, providers may rule out sleep apnea because it is so closely association with obesity. However, this is less true in the SCI population, in which thin people are also likely to have sleep apnea.

- It is difficult to get sleep studies done in the hospital because of other medical conditions, tracheostomies, etc.

- “Benign neglect”: staff assume all patients with quadriplegia breathe shallowly or slowly, not that they might have apnea.

- Reluctance to add another complicated treatment to the patient’s life

- SCI specialists may not be familiar with sleep apnea and its treatments.

- Sleep medicine specialists mostly see obstructive sleep apnea in obese people with chronic health conditions and are less likely to have experience with SCI patients.

- Sleep labs are not set up to deal with SCI: some are not accessible; mattresses may not be protective enough; and personal care may have to be done in the middle of the night. Finally, many hospitals don’t have sleep labs.

Treatment

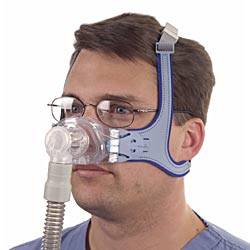

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy

- This is the most common treatment.

- A mask is positioned over the nose or the nose and mouth.

- A bedside pump provides pressurized air, which keeps the upper airway “inflated” so it does not collapse while breathing.

- There are many different varieties of masks, and a person may need to test several before finding one that is tolerable.

Bi-level positive airway pressure (BiPAP) is a variation on CPAP.

- Pressure alternates between a higher pressure while breathing in and lower pressure while breathing out.

- It synchronizes with your effort to breath and is often used for central sleep apnea or weakness of breathing muscles.

- For some patients, the effect is much like being on a ventilator, but the air comes through a non-invasive interface such as a mask, instead of a tracheostomy.

Other treatments

- Oral appliance that pulls your jaw forward and tugs your tongue and other structures forward to give more room in the upper airway.

- Let gravity help you by sleeping on your stomach, if you are able to breath in that position.

- Surgery

- UPPP (uvulopalatopharyngoplasty) to remove excess tissue obstructing the airway.

- Jaw lengthening surgery that pulls the tongue forward.

Treatment acceptance

CPAP is very effective, but sleeping with a mask over your face usually takes a lot of getting used to. In a study at the Seattle VA of 40 patients diagnosed with sleep apnea, 20 patients were using CPAP or BiPAP and reported that it was very helpful (average 8.9 in a 0–10 scale) and minimally unpleasant (3.1 on a 0–10 scale). For those patients in the group who didn’t use it, discomfort from the mask was the most common complaint. Some said they just couldn't sleep or sometimes even breathe when the mask was on them. Others said it made them claustrophobic.

Avenues for future research

There are many unanswered questions about sleep apnea and SCI that need investigating, such as:

- Since the incidence of sleep apnea is so high in this population, should everyone with a SCI be screened routinely?

- What kind of diagnostic study is the most accurate and practical?

- What medications (such as oral baclofen for spasticity) have the worst impact on sleep apnea, and what can be used instead (for example, intrathecal baclofen)?

- Is weight loss beneficial in this population, as it is in the general population?

- Should BiPAP be the first choice treatment for this population, rather than CPAP?

- Is surgery a good option, especially since many patients with SCI likely have minimal airway obstruction?

- What is the role of oral appliances in managing sleep apnea in SCI?

- How can sleep labs be modified for this population?

- What sleep medicine services and providers should be a regular part of SCI care in hospitals?