SCI Forum Reports

Back Pain, Wheelchair Seating and Posture

May 13, 2003

Are back and shoulder pain an inevitable consequence of using a wheelchair for people with spinal cord injuries? Jennifer Hastings doesn't think so, and she's on a crusade to change the way patients, providers and manufacturers think about wheelchair seating.

Hastings is a physical therapist who specialized in SCI rehabilitation for 13 years. She established the wheelchair seating clinics at both the VA and Harborview Medical Centers. She has lectured and published widely on the subject and is recognized as a national expert.

The reason pain is so common among wheelchair users with SCI, Hastings believes, is that "we've forgotten the skeleton and dealt with all neurological patients-SCI, stroke, Parkinson's-as if they are only a nervous system." She thinks close attention to the skeleton and proper postural alignment can alleviate or avoid many of the typical musculoskeletal pain problems in this population.

The obvious purpose of a wheelchair for people with SCI is to provide mobility, but a less recognized need is to provide stabilization of and substitution for weak (or absent) trunk muscles during sitting and functional activities. "If you don't have use of your trunk muscles (abdominals and back extensors), as in a cervical injury" Hastings said, "you don't have an anchor to your wheelchair."

To feel more stable, people slump back and slide the buttocks forward in the seat. "That's very stable," said Hastings, "but you can't sit that way all day without eventually developing posture-related pain problems."

The traditional 90/90 wheelchair (seat parallel to the floor; high seatback at a 90 degree angle to the seat) sets people up for this kind of posture problem from day one, Hastings claimed. (See Figure 1.) "Some facilities are still prescribing these for people with SCI, and it should not be allowed."

|

Figure 1: The traditional wheelchair configuration (still used in many medical centers), with a backrest that stops at the upper back and a backrest angle to the floor of 90 degree, causes the buttocks to slide forward and the neck to thrust frontward. Proper alignment of ears over shoulders over hips is not possible in this configuration. |

One way to increase stability in a wheelchair is to recline the backrest or tilt the chair in space. While this allows the lower back to stay against the seat back, it also thrusts the neck forward, which quickly becomes fatiguing and painful for the neck muscles.

Whether standing or sitting, proper postural alignment places the ears over the shoulders over the hips while maintaining normal spinal curves. This alignment is optimal because "it takes the least muscular work to maintain," Hastings explained. Less muscular work means less fatigue and pain and more functionality.

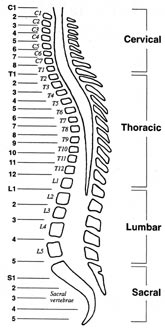

The normal spine curves out (toward the back) slightly in the thoracic (middle back) region and curves inward slightly in both the cervical and lumbar areas.

The normal spine curves out (toward the back) slightly in the thoracic (middle back) region and curves inward slightly in both the cervical and lumbar areas.

Hastings believes that maintaining and supporting these natural curves allows for stability and proper alignment in an upright position. She achieves this by keeping the back rest angle at (or as close as possible to) 90 degree to the floor, but lowering the backrest height to just below the thoracic curve; making sure the bottom of the backrest contacts the lumbar region; and tipping the seat up in front, resulting in a seat angle that's slightly more acute than 90 degree. (See Figure 3.)

|

|

|

| Figure 3 : Proper ears-over-shoulders-over-hips alignment is achieved in this wheelchair configuration. | ||

Frequently the lowered backrest height meets with resistance from other clinicians. "I've had many arguments with doctors who say, 'You can't have a backrest that low-they're jelly above that!'" Hastings recounted. "But it's jelly that I want to align this way to allow the person to use the strength they have." In case after case, she has found that maintaining a normal thoracic curve and providing lumbar support do provide stability without compromising alignment.

She has the same goals for newly injured patients trying out their first wheelchair while still in the hospital. "I start with the backrest a little higher and more reclined than I would go (with a long-time injured person)," Hastings said. "But by discharge, the backrest height should be lowered and the angle more acute."

The concept is the same for power wheelchair users. While you need to use a higher backrest for a power wheelchair due to the need for power recline and often driving from a chair "you can still set it up to allow the normal thoracic curve," she said. The key is to support the lumbar spine and have the backrest fall away (rearward) at the thoracic area to allow for the normal spinal curves.

Hastings and many of her patients have noticed that improving posture often results in better overall appearance. In one case, a woman went home after Hastings adjusted her power wheelchair to a more normal upright alignment, and her family immediately noticed a difference. "Her kids said she looked taller, and her husband thought she looked thinner," Hastings recalled. "Posture is also about vanity." (See Figure 4.)

|

|

| Figure 4: Proper postural alignment often results in improvements in appearance. After this patient went from a poor (left) to proper (right) wheelchair configuration, her family thought she looked taller and thinner. | |

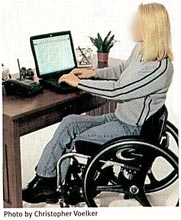

Hastings also cautions patients against forming bad postural habits that often occur while performing routine activities. Computer users, for example, usually position the keyboard too far away; as a result, they have to slump down in order to avoid pitching forward. "The keyboard should be positioned close to you so you aren't reaching out," said Hastings. "If you're an all-day keyboard user, I recommend using a strap to give you a little support." Crossing the legs while typing twists the torso and cuts off circulation if maintained for too long. "You should adjust your posture to different tasks throughout the day," Hastings continued. "It's good to shift your position around frequently." (See Figure 5.)

| Figure 5: This keyboard is too far away from the user, causing her to reach forward awkwardly. Crossing the legs twists the torso and restricts circulation. |  |

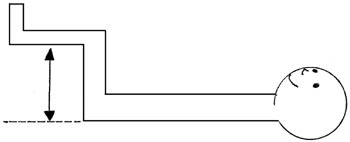

A seat cushion that's too long is a common mistake in wheelchair configuration. Recently the standard length of the seat cushion was increased to 18 inches (too long for all but the tallest people) because a longer seat was thought to distribute seat pressure over a larger area and reduce the risk of skin problems. The longer seat can also make transfers easier. But Hastings believes a seat that is too long makes good upright posture impossible. "Unless you're really tall, it makes you sit with your buttocks forward and your pelvis tilted posteriorly." The seat should not be any longer that the distance between the small of the back and the bend in the knees. (See Figure 6.) You can learn a new transfer technique or buy a seat cushion designed to reduce pressure, Hastings said, but good posture should not be compromised. Poor posture causes pain.

|

| Figure 6: Seat depth should NOT exceed thigh length. |

How does poor posture cause pain?

Pain develops when muscles are asked to do a job they aren't designed for and to "stand in" for muscles that are paralyzed, Hastings explained. There are two types of muscles: tonic, for holding (the postural muscles); and phasic, for mobility (the task-oriented muscles). "They are union workers," she said. "They don't like to do things not in their job description. With paralysis, there are fewer muscles available to work, and the remaining muscles are asked to do work they weren't designed for physiologically. Asking phasic muscles to hold and tonic muscles to move results in pain and fatigue." In addition, if these muscles are doing a different job, they are not available to do their own job. This situation compromises functionality.

Muscles also have a length they like to operate in, and if they are stretched or shortened due to poor posture they become weak. "Poor posture sets up and exacerbates muscle imbalances," Hastings said.

The key, then, is to make sure the wheelchair is configured properly to give adequate trunk support and stability so the non-paralyzed muscles do not become fatigued and painful from doing too much or doing the wrong job. Pay attention to the skeleton so the muscles can do their job, Hastings said. "That's the take-home message."

Further reading:

- Hastings, JD. Seating Assessment and Planning. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2000 Feb;11(1):183-207, x. Review.

- Hastings JD, Ranucchi ER, Burns SP. Wheelchair Configuration and Postural Alignment in Persons With Spinal Cord Injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003 Apr;84(4):528-34.