Spinal Cord Injury Update

Fall 2012: Volume 21, Number 3

SCI-CARE Study: Finding better ways to care for SCI patients

The Northwest Regional Spinal Cord Injury System (NWRSCIS) is starting an exciting new study that hopes to improve the lives of individuals with spinal cord injuries (SCIs) by doing a better job of managing three common, inter-related health problems: chronic pain, physical inactivity and depression.

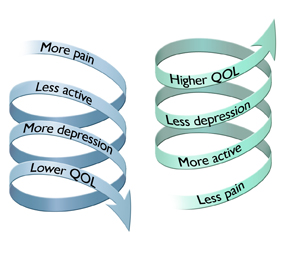

“We know from our clinical experience, consumer feedback, and the research literature that these three conditions are widespread, difficult to treat, often chronic, and can have a very negative effect on quality of life,” says Chuck Bombardier, PhD, professor and psychologist in the UW Department of Rehabilitation Medicine and director of the NWRSCIS. Bombardier is the lead investigator for this new study, called SCI-CARE. “These problems are interwoven,” he adds. “Individually and together they can create a downward spiral toward poor quality of life. But we are betting that if we treat them in a more coordinated way, we can create an upward spiral toward better quality of life.” (See figure on right.)

About 63% of individuals with SCI have chronic pain, and research has shown that pain is related to poorer quality of life. Pain also seems to trigger depression and frequently keeps people from being more active. Standard medical treatments are beneficial but often not a cure. Non-medical treatments have been found to help but are underutilized. For example, cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain can be very effective in decreasing pain and improving mood, but few people actually receive this type of treatment.[1]

Physical inactivity is also a major problem after SCI. Prior to injury many people with SCI were physically active, but after injury about 50% of people with SCI do not engage in any leisure time physical activities.[2] That is, they never go for a wheel or walk, don’t play a sport, don’t exercise at home or go to a gym. Inactivity contributes to poor quality of life as well as obesity, diabetes, heart disease and accelerated aging.[3] Many studies have shown that exercise improves strength, endurance and mood in SCI. There are now published physical activity guidelines for people with SCI.[4] However, within the standard rehabilitation care system, we have limited capacity to help people meet those guidelines.

Depression is not something that people with SCI talk a lot about, but it is there in the background for about one in five people.[5] Depression often lasts for years and is associated with poorer satisfaction with life.[6] Few people receive adequate treatment for depression through medications or counseling. Physical exercise can be an effective treatment for depression but is rarely used.[5]

As described above, interventions for pain, depression and inactivity exist, but many patients do not receive them. “Lack of resources, inconvenience and limited transportation likely contribute to under-treatment,” Bombardier explains. “But the way medical care is organized also plays a role. Most medical care is set up to treat acute medical problems that can be ‘cured’ with medications or surgery. We are not organized as well to help people manage chronic conditions or make lifestyle changes.”

Innovative approach

For this reason, Bombardier and his colleagues decided to study an alternative way of organizing how we provide treatment for pain, inactivity and depression called “collaborative care.” Collaborative care has been used successfully in people with heart disease, diabetes and chronic pain but has not been tested in SCI. Collaborative care produces better medical outcomes (e.g., blood sugar control, blood pressure), better patient outcomes (e.g., lower depression and pain scores and higher satisfaction with care) and in some cases, lower costs.[7,8,9] With this in mind, “we decided on a ‘real world’ experiment that tests the effectiveness of providing collaborative care within our outpatient SCI rehabilitation clinics compared to usual care,” Bombardier says.

The collaborative care approach used in the SCI-CARE study was developed here in Seattle by Dr. Wayne Katon and colleagues (http://www.teamcarehealth.org). Collaborative care uses a team of expert clinicians with complementary skills working closely together to care for patients with complex medical conditions, such as persons with SCI.

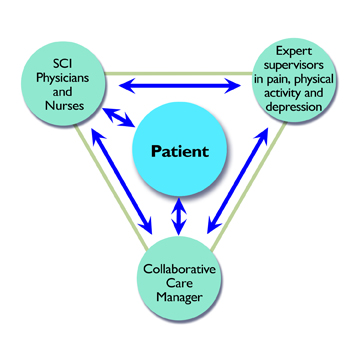

Central to the SCI-CARE team is a care manager who works with each patient along with his or her regular multidisciplinary rehabilitation team to ensure that the patient gets state-of-the-art care for these three conditions. (See figure on right.) The care manager assists the patient and medical team in several key ways:

- Identifying specific goals the patient wants to achieve, such as reducing pain by at least 50% or exercising for 20 minutes three times per week.

-

Checking in with patients to measure progress and identify any problems that arise between doctor visits. This information is fed back to the physician so treatment adjustments can be made more quickly and with less hassle for the patient.

- Acting as a counselor and coach to help patients achieve their goals.

- Receiving weekly supervision from experts in pain, exercise and depression to ensure the patient receives optimal care and meets his or her goal. These experts suggest treatment adjustments to the care manager and to the physician to help the patient meet the goal.

Study procedures

The study is a 16-week randomized controlled trial comparing collaborative care to usual care for improving physical activity, chronic pain and depression. Study participants will be randomly assigned to one of two groups. The first group will receive the same care that they would normally receive in our rehabilitation clinics (the “control” group). The second group will receive follow-up from a care manager (the “intervention” group).

Participation involves visits with the patient’s doctor or nurse, in-person and telephone contact with the care manager, and answering questions from a research study assistant. At the end of the 16 weeks, the care manager will help participants develop a plan to maintain health improvements that have been made.

Who can participate

To be eligible for the study, participants must be outpatients at the SCI clinics at Harborview or University of Washington Medical Center, at least 18 years old, and have significant problems in one or more of the three areas of pain, depression or inactivity.

Results

Since improvement in quality of life (QOL) is the goal of this study, the researchers will use QOL questionnaires specifically designed for the SCI population to determine whether the SCI-CARE intervention is better than usual care for managing pain, depression and inactivity in persons with SCI. Questionnaires will be administered to participants over the phone or in person before and after the 16-week study period, and again at 32 weeks to see if improvement has been maintained.

If results show that the collaborative care method is better than usual care, is it likely to be adopted by SCI providers and the health care system in general? Bombardier is hopeful, but some of it will depend on the bottom line. “We will look at the costs versus benefits of the intervention as one of the outcomes,” he says. “If the benefits outweigh the costs, there is a greater likelihood that this model could be adopted and paid for by insurers.”

Find out more

If you are interested in participating or want to learn more, call 206-744-3608 or send an email to scicare@uw.edu. (Study staff cannot guarantee the confidentiality of information sent via email.)

References

- Jensen MP, Barber J, Romano JM, Hanley MA, Raichle KA, Molton IR, Engel JM, Osborne TL, Stoelb BL, Cardenas DD, Patterson DR. Effects of self-hypnosis training and EMG biofeedback relaxation training on chronic pain in persons with spinal-cord injury. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2009 Jul;57(3):239-68.

- Ginis KA, Latimer AE, Arbour-Nicitopoulos KP, Buchholz AC, Bray SR, Craven BC, Hayes KC, Hicks AL, McColl MA, Potter PJ, Smith K, Wolfe DL. Leisure time physical activity in a population-based sample of people with spinal cord injury part I: demographic and injury-related correlates. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010 May;91(5):722-8.

- Nash MS. Exercise as a health-promoting activity following spinal cord injury. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2005 Jun;29(2):87-103, 106.

- Ginis KA, Hicks AL, Latimer AE, Warburton DE, Bourne C, Ditor DS, Goodwin DL, Hayes KC, McCartney N, McIlraith A, Pomerleau P, Smith K, Stone JA, Wolfe DL. The development of evidence-informed physical activity guidelines for adults with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2011 Nov;49(11):1088-96.

- Fann JR, Bombardier CH, Richards JS, Tate DG, Wilson CS, Temkin N; PRISMS Investigators. Depression after spinal cord injury: comorbidities, mental health service use, and adequacy of treatment. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011 Mar;92(3):352-60.

- Hoffman JM, Bombardier CH, Graves DE, Kalpakjian CZ, Krause JS. A longitudinal study of depression from 1 to 5 years after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011 Mar;92(3):411-8.

- Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, Ciechanowski P, Ludman EJ, Young B, Peterson D, Rutter CM, McGregor M, McCulloch D. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010 Dec 30;363(27):2611-20.

- Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Nov 27;166(21):2314-21.

- Katon W, Unützer J, Fan MY, Williams JW Jr, Schoenbaum M, Lin EH, Hunkeler EM. Cost-effectiveness and net benefit of enhanced treatment of depression for older adults with diabetes and depression. Diabetes Care. 2006 Feb;29(2):265-70.