SCI Forum Report & Video

Management of Urinary Problems Caused by Spinal Cord Injury

Presented on October 13, 2009, by Stephen Burns, MD, Staff Physician, SCI Service, VA Puget Sound Health Care System, Associate Professor, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Washington. In addition, two individuals with spinal cord injury talked about their personal experiences with bladder management problems and solutions. Read the report or watch the video on this page.

Presentation time: 65 minutes. After watching, please complete our two-minute survey. Thank you!

You can also watch this video on YouTube with or without closed-captioning.

For a complete list of our videos, click here.

Report

Management of Urinary Problems Caused by Spinal Cord Injury

Stephen Burns, MD, Staff Physician, SCI Service, VA Puget Sound Health Care System, Associate Professor, Dept. of Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Washington

- How the urinary system works

- How we figure out what the bladder is doing

- Choosing the best method of bladder drainage

- No catheter in the bladder

- Bladder emptying for males: Open the sphincter

- Intermittent Catheterization (ICP)

- Indwelling Catheter

- What’s different about females?

- Considerations: What's the best method for you?

- Other surgical options

- Functional electrical stimulation (FES)

- Botulinum toxin injection to the bladder

- Table: Most common methods of urinary drainage

- Urinary complications

- Screening tests

- UTIs, antibiotics, cranberry and methenamine

- Personal experiences: Tammy Wilber and Todd Stabelfeldt

Before 1940, most people with spinal cord injuries died from urinary tract infections in the first few months after injury. After the introduction of antibiotics in the 1940's, people started surviving longer, but renal complications continued to be a problem and kidney failure became the leading cause of death. With current management practices and periodic testing, things have improved greatly, and now fewer than 3% of people with SCI die from kidney failure.

How the urinary system works

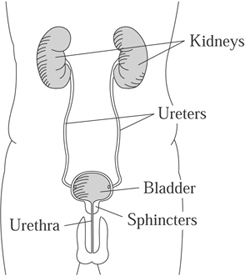

The upper urinary tract consists of the kidneys, which filter the blood and produce urine, and the ureters, which connect the kidneys to the bladder. The upper tract is not directly affected by spinal cord injury.

The lower urinary tract has muscles which are affected by the spinal cord injury: the bladder muscle (detrusor) and the valve muscles (sphincters). The urethra connects to the outside of the body where the urine passes through.

In normal urination, the bladder is either filling or emptying. The bladder is relaxed as it fills with urine, and the sphincter stays closed during this time so the urine doesn’t leak out. When it’s time to empty, the bladder contracts and the sphincter relaxes so the urine can flow out. Most of the time the bladder is relaxed and filling as urine is made. The bladder and sphincter muscles are automatically coordinated to contract and relax at the correct time. These are reflex patterns wired into the brainstem and spinal cord.

After spinal cord injury, several different kinds of urinary problems can result, depending on the level of injury and which nerves and reflexes have been disrupted. Bladder and sphincter muscles may be weak, overactive or poorly coordinated.

Essentially, two basic problems occur. Filling problems (incontinence or leaking) occur when the bladder is overactive and contracts too much or at the wrong time, or the sphincter doesn’t contract enough to keep the urine from leaking out. Emptying problems (retention) occur when the bladder doesn’t contract enough or the sphincter won’t relax. Treatment will depend on what kind of problem you are having.

How we figure out what the bladder is doing

- We can get a lot of the information just starting with the history of when and under what circumstances incontinence occurs.

- A neurological exam can tell us what is happening with the whole nervous system in terms of strength, sensation and reflexes. This gives us a good picture of what is likely to be happening with the nerves to the bladder and sphincter, what is working and what's contracting and what's not.

- A postvoid residual test shows how much urine remains in the bladder after voiding (emptying). This can be done using a catheter or by ultrasound.

- A group of tests called urodynamics tells us more precisely what the nerves and bladder are doing during filling and emptying. These tests require the bladder to be slowly filled with fluid through a small catheter, while the activity of different muscles is measured. Urodynamics help answer these types of questions:

- Is the bladder relaxing enough to allow it to fill up with urine?

- Is the sphincter opening at the right time?

Choosing the best method of bladder drainage

The goal in choosing a method of bladder drainage is to find the simplest, most convenient and least expensive method that will keep you dry, avoid serious complications and treatment side effects, and preserve your kidneys for your entire life. There are several different methods, depending on your injury and circumstances, and almost all of them give good outcomes, with just a few exceptions.

No catheter in the bladder

- Voluntary voiding (bladder emptying) under normal control, possible in combination with medications to calm an overactive bladder muscle if necessary.

- Involuntary voiding, where the bladder fills to a certain point, kicks off and empties. Emptying might occur spontaneously or in response to pressure on the bladder such as tapping the bladder (Crede) or bearing down (Valsalva). These are NOT recommended for most patients, however, because they can cause problems such as high pressure that can damage the kidneys. For males, a condom catheter can be used to collect the urine.

Bladder emptying for males: Open the sphincter

There are a few methods for keeping the sphincter open so urine can flow freely from the bladder into a condom catheter.

- Sphincterotomy: Surgically cut and open the sphincter. Scarring can occur over time, and the surgery may need to be repeated. It can also worsen erectile dysfunction.

- Botox injected into the sphincter. This needs to be repeated every three to nine months, and as it wears off there is an increased chance for urinary retention.

- Urethral stent (small steel tube) placed in the sphincter. Disadvantage are that the stent can move around or tissue may grow into it and block the flow or urine, requiring corrective surgery.

Methods that keep the sphincter open only work for people whose bladders are able to contract, allowing urine to continuously drain into a collection device like a condom catheter. If your bladder does not contract, the urine won’t drain out, and you are at risk for infection.

The downside of any sphincterotomy method is that the bladder may lose its ability to contract and urinary retention may develop over time. Also, condom catheters are not without problems. They can be hard to keep in place, and some patients will need to have a penile prosthesis put in so there is enough penis for the condom to attach to. And even though the condom catheter does not involve a tube going into the bladder, it does not seem to result in fewer UTIs than indwelling or Foley catheters.

Intermittent Catheterization (ICP)

This method is also known as ICP (Intermittent Catheterization Program), CIC (Clean Intermittent Catheterization) and I & O (In and Out) catheterization. With this method, you insert a catheter into the bladder and empty it completely every four to six hours. The goal is to cath frequently enough to keep urine volumes in the bladder lower than 500 ml. This method requires that you closely monitor your fluid intake, usually around 2 liters per day, otherwise you might be cathing too frequently to make this practical.

ICP is a preferred method for patients who have enough hand function (usually C7 and below, or C6 for motor incomplete injuries) to perform it independently and who can remember to cath on schedule. It is the closest thing to the normal bladder function, where the bladder fills continuously for a period of time and then empties all at once. This method reduces the risk for infections because there isn’t enough time for any bacteria left in the bladder to reproduce enough to cause symptoms.

Complications of ICP include narrowing of the urethra from passing the catheter through frequently. More rarely, inflammation of the epididymis (a duct that stores sperm) , hydronephrosis (enlargement of the urine collection section of the kidney) and reflux (backup of urine into kidney) may occur.

ICP is not usually a good method for someone who is unable to perform it independently. Having someone else cath you increases your risk for infections and also reduces your independence, since you need someone with you to perform the ICP.

Anticholinergic medications, such as oxybutynin (Ditropan) or tolterodine (Detrol), may be necessary to inhibit bladder contraction. Botox injection to the bladder muscle can also be used for this purpose.

Indwelling Catheter

An indwelling catheter is a common bladder-emptying method for those who cannot perform ICP. A tube is inserted into the bladder, where a balloon on the end holds it in place. It remains in the bladder and drains constantly into a container, such as a leg bag. There are two types of indwelling catheter:

- Foley catheter: the tube is inserted through the urethra.

- Suprapubic (SP): the tube goes through a hole in your abdomen.

Advantages:

- It will usually empty the bladder and keep you dry regardless of what kind of bladder or sphincter problems you have.

- Even those with higher level injuries can be completely independent—once you're set up, even if you have a high level injury, you can use an electric leg bag opener to empty out urine and not need assistance from anybody all day long.

Disadvantages:

- Having a catheter sitting in the urethra all the time can cause urethral erosions, which is often a reason for switching to a suprapubic tube.

- The suprapubic tube requires surgery, and sometimes the bladder neck needs to be closed to prevent leaking.

- There is a catheter coming out of your body and a bag of urine with you all the time. Some people just don’t want that.

- Increased risk of bladder cancer and bladder stones.

- More infections than with ICP.

What’s different about females?

Because women have no penis, collecting urine is more difficult. There is no good external collection device, like a condom catheter, for women. Women doing ICP have more problems with incontinence than men because the female urethra is short and more likely to leak urine.

Women get different complications from having an indwelling Foley catheter for a long time. The urethra can become dilated (larger), which results in more leakage. Switching to a larger catheter just dilates the urethra more, causing more incontinence. For this reason, a suprapubic (SP) tube is a good option for a woman who otherwise would be using a Foley catheter.

What is the best method for you?

Considerations:

- Do you have the hand function to do ICP independently?

- How much mobility is required? For example, does the method require transferring to a toilet?

- How much of the day is going to be devoted to bladder management?

- What are the risks if you don’t follow the program? Are you likely to comply?

- Do you live in a remote location with no follow-up around, or are you close to specialized medical care?

- What's the likelihood that you would benefit from one of the more complicated, more time-intensive techniques?

Other surgical options

- An artificial urinary sphincter can be placed if there is incontinence due to the sphincter being open. This is a device that is surgically implanted in the body to substitute for the sphincter muscles. They have not been used commonly in people with SCI, since implanted devices are prone to infection, but some urologists do recommend them for certain individuals with SCI.

- Bladder augmentation, which uses a piece of the bowel to enlarge the bladder, may be a good option for someone doing ICP whose bladder doesn’t hold enough urine in spite of medications.

- Urinary diversion (diverting the urine away from the urethra)

- Urostomy, which uses a piece of bowel to create a connecting tube from the bladder to the outside of the body (like a colostomy does for stool). Urine drains out and collects into a bag fastened to the opening (called a stoma). This is usually a fall-back method in cases where there have been major complications that cannot be treated with other methods.

- Catheterizable stoma (Mitrofanoff) creates a thin tube from a piece of bowel that connects the bladder to the abdomen where a person can insert the catheter to drain the bladder (rather than inserting the catheter through the urethra).

Functional electrical stimulation (FES)

This system allows emptying without using a catheter. A surgically implanted stimulator and electrode trigger the bladder to squeeze when you flip a switch on an external stimulator. It requires cutting the sacral nerve roots, and you need to either use a condom catheter, a hand urinal, or transfer onto a toilet when the system is turned on. It can also be used to stimulate a bowel movement. It was on the market in the US (called the Vocare System) for a short time and continues to be available in Europe.

A new FES system currently under development at Case Western in Cleveland uses an electrode to block the sacral sensory roots so that you wouldn't need to cut the nerve roots. Somebody with an incomplete spinal cord injury could potentially use this method.

Botulinum toxin injection to the bladder

If oral medicines (anticholinergics) are unable to relax the bladder muscle enough for a person to do ICP, Botox injections to the bladder muscle can accomplish this. Botox is effective for about six to nine months. When it begins wearing off, you start having incontinence and need it done again.

Most common methods of urinary drainage five years after injury (SCI Model Systems data)

|

Males |

Females |

SP Tube |

10% |

7% |

Foley |

11% |

23% |

Condom Catheter |

17% |

0% |

ICP |

29% |

26% |

Normal |

22% |

28% |

Urinary complications

Kidney and bladder stones

Stones are common in people with SCI. They can develop early on because large quantities of calcium leave the bones in the first few months after injury. It is more common to get stones later, and this is due to infections over the long term. Bacteria break down urea into chemicals that form stones, which can cause blockages, kidney damage and serious infections.

Hydronephrosis and reflux

These are similar conditions involving either a blockage of urine or a backwards flow of the urine up toward the kidney. It can have multiple causes, and the treatment is to remove whatever is blocking the system and to reduce the bladder pressure.

Bladder cancer

There is a small risk of bladder cancer for individuals using indwelling catheters. Screening recommendations are controversial since we don’t know who needs to be screened, how often, and how soon after injury. Unfortunately, these tend to be such aggressive cancers that even yearly screening won’t catch all of them because they grow so fast. Fortunately, bladder cancer is not very common.

Screening tests

We use a variety of tests to detect problems in the urinary system.

Lab tests

- Serum creatinine (blood test): Creatinine is filtered out by the kidneys. A high level in the blood means the kidneys are not filtering enough. To be useful, results must be monitored over time to see if there are changes. If it starts rising, it’s a sign something is wrong with the kidneys.

- Creatinine clearance: 24-hour urine collection to see how much filtering the kidneys are doing over time. This test may not give reliable results. Other lab tests are being studied as well to see what is best for screening.

Imaging tests

- Ultrasound is a radiation-free, risk-free way to pick up on stones or blockages.

- CT scan of the kidneys, ureters and bladder (CT-KUB): uses lots of radiation and may carry a one in 3000 chance of producing a fatal cancer. While not recommended as a routine test, it is useful in specific situations.

- Renal scan: used to show kidney function, but image is fuzzy.

How often should the test be done?

Research has not established what testing should be done for everyone and how often. To some extent it should depend on the patient and what kinds of problems he or she is having. While early screening is not necessary for those who have fairly normal control of bladder, good sensation and not having symptoms, most people with spinal cord injury should have some sort of periodic testing of their urinary tract to detect problems before they become big problems.

The Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine publishes a guideline for physicians stating that screening is usually done annually. However, since research has not established the necessary frequency for the screening tests, the guideline does not make a strong recommendation about how often the tests must be done. (Bladder Management for Adults with Spinal Cord Injury: A Clinical Practice Guideline for Health-Care Professionals, www.pva.org).

UTIs and antibiotics

When considering the use of antibiotics for UTIs, it is important to distinguish between actual infections and colonization.

- If you have bacteria in the urine (found through a lab test) AND have symptoms (fever, pain, spasticity), then you have an infection that needs to be treated with antibiotics.

- If you have bacteria in the urine but have NO symptoms, then you have what is called “colonization” and you should not be treated with antibiotics.

In general, treatment should be based on symptoms, rather than on bacterial count alone. Some bacteria don’t cause any symptoms, and their presence in the urine might even be keeping out other bacteria that could cause problems. In fact, there is currently some promising research into this idea of “bacterial interference” to determine whether inoculating people with a specific, relatively harmless bacteria will keep harmful bacteria away.

Prophylactic antibiotics, or taking antibiotics all the time to prevent UTIs, have not proven to be beneficial in research studies and can result in the proliferation of resistant bacteria that are hard to treat. A substance called methenamine, which turns into formaldehyde in the bladder, is used by some patients to try and reduce infections.

Cranberry (juice or tablets) has also been studied as a way of preventing UTIs. Usually the tablet form is used since drinking cranberry cocktail is so full of sugar and calories. Although cranberry has not proven effective in clinical trials with people who have SCI, it does seem to help some individuals. As with many aspects of bladder management after SCI, finding what works is often a matter of trial and error.

Personal Experiences

Tammy Wilber

Tammy sustained a T5 complete spinal cord injury as a result of a car accident when she was 17. She also lost her right kidney in the accident, which had important implications for her bladder management.

“For the first couple of years after my injury, I had a lot of problems with cathing,” she said. “I was still not independent in cathing myself when I went home after two months in rehab. This was very frustrating. I was incontinent all the time. No medications were working for me. I wasn't drinking enough because I didn’t want to pee in my pants. Women have smaller bladders, and mine was completely spastic.” She went back to her senior year in high school wearing diapers and having frequent bladder accidents. She also had to wake up every four hours to cath and couldn't sleep through the night.

Tammy heard about bladder augmentation and looked into it. “It’s a big surgery, so you need to research it and make sure it’s going to be the right thing for you,” she said. She was still living in New England (where she grew up) at the time, and found a doctor with significant experience doing these surgeries. A piece of her intestine was used to enlarge her bladder, and her appendix was used to create a canal from her bladder to a stoma (opening) on her abdomen.

“The stoma just looks like a little second belly button. It kind of works like a sphincter, where I insert the catheter. Nothing leaks out of the stoma. I'm on no bladder medications. Basically they just kind of rerouted everything, and so I'm kind of like a guy now because I can pee anywhere! I have a couple of UTIs a year.” She doesn’t have to pull down her pants and transfer to a toilet. She can sleep through the night. It makes things like traveling much easier. And she can drink all the water she needs without worrying about accidents. “It has really increased my quality of life.”

This procedure was a big surgery and required a long recovery, “but the result is that I'm healthier, and my kidney is healthy,” Tammy said. “It's just been great.”

Todd Stabelfeldt.

Todd became paralyzed in 1987 at the age of eight due to a gunshot wound. “A cousin shot me by accident, and the result was C4 complete quadriplegia. I can move and feel from the shoulders up, and anything else is just pretty much dead.”

Todd requires assistance with his bladder program. He started with the condom catheter. This program added about 45 minutes to his morning routine and didn’t always keep him dry. He also had recurrent UTIs. These became increasing problems over the years and interfered with his work and health. “It actually got to the point where I could smell the aroma of E. coli versus pseudomonas, and I could tell the physician which bacteria was in my bladder and what antibiotic I needed.” He was on antibiotics almost all the time and it wasn’t working.

After many consultations with urologists, he ultimately decided in 2007 to have suprapubic catheter surgery. “And it's been just one huge blessing from that point forward. There was lots to learn, and it took me about six months to get comfortable with the SP tube, trying to understand how much water to drink, what size catheter do I put in there, et cetera, et cetera. I feel very comfortable with it now. I'm able to tell if my bladder is becoming spastic. I can tell if I'm symptomatic for an infection and if I need antibiotics for a couple days, and when my SP tube needs to be changed.” He doesn’t worry about incontinence, and he is able to be more independent. “It’s been a huge, huge asset for me.”