SCI Forum

Protecting Your Shoulders and Staying Active After Spinal Cord Injury

Presented by Kristin Kaupang, Physical Therapist, on April 10, 2012 at the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, WA.

[Check out the September 25, 2019 SCI Forum Revolutionay Shoulder Care for SCI.]

You can also watch this video on YouTube with or without closed-captioning.

Presentation time: 62 minutes. After watching, please complete our two-minute survey!

For a complete list of our streaming videos, go to http://sci.washington.edu/videos.

Report

Contents

Shoulder pain and SCI

As we all know, there are many changes in how muscles are used after spinal cord injury. Often a person has to rely completely on their upper extremities for what their legs used to do. In individuals with complete injuries, the upper body has to perform activities meant for the legs. For people with incomplete injuries, there may be altered strength or altered sensation, and they may use their muscles a little bit differently. Over time, these abnormal stresses can cause pain or discomfort.

The shoulder is an extremely flexible joint. The ball and socket arrangement and large number of tendons and ligaments allow an almost infinite number of directions the shoulder can move in (witness the astonishing contortions in a pitcher’s arm when throwing a baseball). While this enormous range of motion is great for function, it makes the shoulder especially vulnerable to damage.

Around 75% of individuals with SCI have shoulder pain at some time during their lives, and the rate increases with the number of years since spinal cord injury. Shoulder pain can be very debilitating, decreasing a person’s independence and lowering quality of life.

How to protect your shoulders

-

REST / stop use of painful extremity

-

Change the way you perform tasks

-

Modify environment of task performance

-

Strengthen and maintain flexibility

PLEASE NOTE: Consult with your physician or physical therapist before practicing the positions, exercises or stretches in this report to make sure you are doing them correctly for your specific condition, health and injury.

1. Rest or stop using your shoulder

Since everything you do involves your shoulders—getting out of bed, rolling, sitting, transferring—it's almost impossible to completely stop using your upper extremities unless you go on bed rest and have full caregiver support. This isn’t an option for most people.

Instead, you should strive to minimize shoulder activity (for partial rest). This involves paying close attention to your daily activities and figuring out what you can change, such as:

- Decrease the frequency of movements that cause pain. Plan ahead to minimize the number of times a day you have to do something, like opening a door or reaching into a cabinet.

- Use your non-dominant or non-painful extremity for basic tasks, such as eating or opening doors.

- Ask for some help with tasks that cause pain.

- Try to make your movements as efficient as possible, such as positioning your body in a way that brings you closer to something, so you don’t need to reach or move your shoulder as much.

Positioning

Positioning is important, even while resting. Try to keep your shoulders in an “open position,” rotated out, as when you sit upright and squeeze your shoulder blades together in back. This allows more space for all the tendons, nerves and blood vessels coming through the area. When you rotate your shoulders inward—the opposite of the open position—there is less space and more chance of pinching.

These guidelines and illustrations are for general information. Each person will need to adjust according to his or her own levels of pain and discomfort.

Positioning in bed

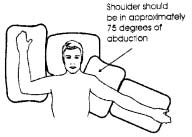

- Back Sleeping: Use pillows and open arm positions as shown in the picture.

Credit: Paralyzed Veterans of America Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Preservation of Upper Limb Function Following Spinal Cord Injury: A Clinical Practice Guideline for Health-care Professionals.Washington, DC:�Paralyzed Veterans of America;�2005.

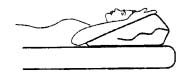

- Side sleeping: Use pillows as shown in the picture. Rather than sleeping directly on your shoulder, rotate slightly to take some of the pressure off.

Credit: Paralyzed Veterans of America Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Preservation of Upper Limb Function Following Spinal Cord Injury: A Clinical Practice Guideline for Health-care Professionals.Washington, DC:�Paralyzed Veterans of America;�2005.

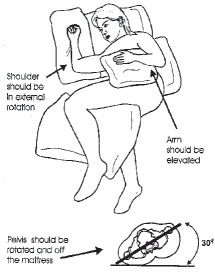

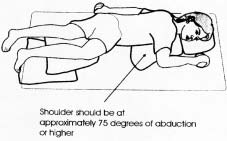

- Stomach sleeping

Again, you want to keep your shoulders in an open rather than closed position. Use pillows as supports to modify your sleeping environment.

Credit: Paralyzed Veterans of America Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Preservation of Upper Limb Function Following Spinal Cord Injury: A Clinical Practice Guideline for Health-care Professionals.Washington, DC:�Paralyzed Veterans of America;�2005.

Remember: Try to keep changing your position throughout the night, about every three to four hours. This is good for your shoulders as well as providing pressure relief for your skin.

Sitting

Avoid sitting with your arms crossed all the time or your shoulders hunched over. Instead, pull or squeeze your shoulder blades together in the back. If you're able to, and it's not impacting your function, try to keep your arms out to the side to prevent your shoulders from getting into a pinched state.

You’ll notice that good posture while sitting gives you greater movement in your arms. Try slumping in your chair and lifting one arm; see how far you can reach. Then sit up as straight as possible, with your shoulder blades squeezed together, and raise the same arm. You get a lot more motion and reach. So a good base of support is essential for shoulder function. If you're sitting slumped in your chair, if you don't have good trunk support, you can easily decrease the amount of shoulder movement you have and cause your shoulders to work harder.

Make sure your seating and positioning has been evaluated by a therapist with expertise in spinal cord injury.

Credit: Paralyzed Veterans of America Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Preservation of Upper Limb Function Following Spinal Cord Injury: A Clinical Practice Guideline for Health-care Professionals.Washington, DC:�Paralyzed Veterans of America;�2005.

2. Change the way you perform tasks

Transfers

Think of the number of transfers you do in a day, multiply that by the year and then by the life span— transfers are a huge part of your ability to stay independent. The more you can protect your shoulders while doing this, the more you preserve your ability to maintain your independence and quality of life.

- Hand placement during transfers— turn your hand outward (open shoulder) when possible, but no more than 30–45 degrees.

- Use a sliding board to allow for smaller movements if large motions are painful.

- Avoid extreme positions. Position your chair in a way that you don’t need to reach way over to transfer.

- Lead with arm experiencing shoulder pain when possible. This may sound odd, but there is actually more force on the trailing arm than the leading arm.

- Use momentum.

- Lean trunk forward as you are able.

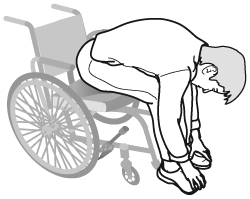

Pressure relief: lean versus press-up

When I first started working in physical therapy, everybody was trained to do the full press-up for pressure relief: grasp their armrests, lift their buttocks clear of their seats, hold for 30 seconds, and do this every 15 to 20 minutes. And while it's still a great technique to relieve pressure, it puts a lot of strain on your shoulders.

Today we recommend that you alternate your press-ups with leaning forward or to the side (see graphic). Side leaning needs to be done on both sides. You can test these methods by having someone reach their hand under your buttocks to make sure there is space there so the pressure relief is effective.

Credit: Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center.

Carry objects close to the body

Holding something with outstretched arms puts torque on your shoulder. If you bring the item closer to you, it’s going to be a lot less strain on your shoulder joint and a lot less painful.

Don’t reach overhead or grab an overhead bar

Reaching overhead or pulling yourself up with a trapeze or a bar puts you into the internal rotation position, closes up the shoulder joint and can lead to pain.

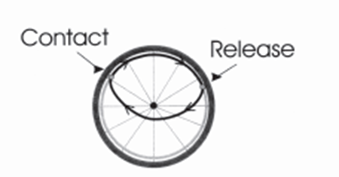

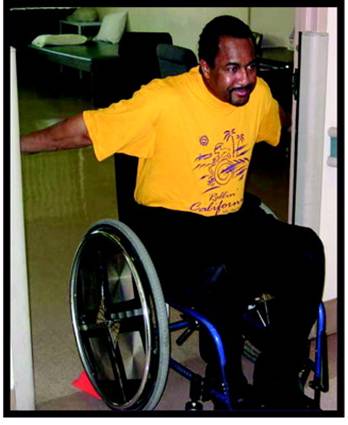

Manual wheelchair mobility

- Use long, smooth strokes. Make sure your contact point on the wheel is at 11 o'clock and your release point is at 2 o'clock. This is more efficient and reduces wear and tear.

- Allow your hand to naturally drift downward at the end of each push stroke to avoid rapid change of direction.

- Avoid rapid forceful impact on pushrim.

- If you lose your momentum going up an incline – turn your chair sideways to rest rather than forcing your shoulders to do it as hard as you can, as fast as you can. Ask for help getting up and down difficult inclines.

- It is important to find a rest position in your chair for your arms when you’re not propelling. People who are unsteady with their balance often use their hands to support their trunk. This is hard on you if you're sitting in your chair for 12 hours a day. Your muscles will become fatigued and wear out faster. If you need to use your arms to sit upright, your positioning should be evaluated so your hands are free to relax or do things.

Power wheelchair users

Try to keep your arms away from your body and stretch them out a little bit when you're in a power tilt.

3. Modify the environment of task performance

- Try to set up your environment so you are transferring to a surface at the same level or downhill from your seat. Transferring to a higher surface is hard on the shoulders.

- Keep things within easy reach.

- Minimize pushing over difficult terrain (inclines and rough surfaces) as much as possible, especially if it is painful when doing so.

- Make sure the tires on a manual wheelchair are properly inflated. This is really important; low tire pressure increases the friction between the tire and the floor, making your chair much harder to push and placing more strain on your shoulders. Check your tire pressure about once a week.

4. Strengthen and maintain flexibility

Several important research studies have shown that certain exercises and routines can help reduce shoulder pain while strengthening and stretching the muscles used for shoulder function. (6, 21, 23, 24) In addition, the American College of Sport Medicine has come out with exercise guidelines for individuals with spinal cord injuries.(1) While there isn’t always complete agreement on how much, how often and which kinds of exercises to do, there are some general guidelines that you can follow to develop strength and stay flexible, depending on your individual situation.

Stretching:

Credit: American Physical Therapy Association. Mulroy, SJ, et al.�Strengthening and Optimal Movements for Painful Shoulders (STOMPS) in Chronic Spinal Cord Injury: A Randomized Controlled Trial.�Phys Ther. 2011:91:305-324.

Muscles that need to be stretched to support the shoulder:

- Upper trapezius

- Pectoralis Major

- Long head of biceps

- Capsular stretches

In general, hold each stretch for at least 20–30 seconds.

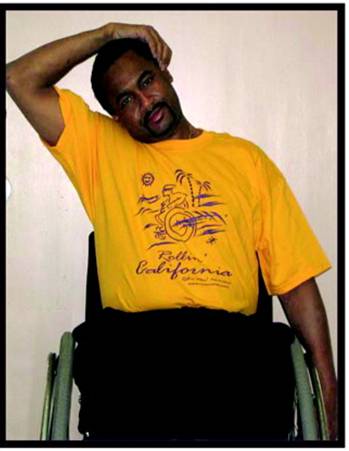

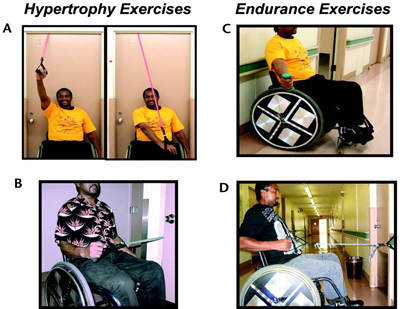

Strengthening

The muscles that move the shoulder blade (scapula) side to side and up and down and stabilize it experience the greatest amount of force throughout the day and need to be strengthened. Bulking up isn’t recommended, as there is a danger of becoming imbalanced and developing more problems.

Credit: American Physical Therapy Association. Mulroy, SJ, et al.�Strengthening and Optimal Movements for Painful Shoulders (STOMPS) in Chronic Spinal Cord Injury: A Randomized Controlled Trial.�Phys Ther. 2011:91:305-324.

Muscles that need to be strengthened to support the shoulder:

- Scapular retraction

- Shoulder external rotation

- Diagonal extension (adduction)

- Scaption

- Serratus anterior

Frequency and Duration of Exercises and Stretches

- In general

- MINIMUM 3–5 days/week for stretching

- MINIMUM 2–3 days/week for strengthening. A couple more times a week is also okay, but be careful to avoid overdoing it. You are using your muscles all the time every day during propulsion and other activities, so they do need rest.

- In addition, 3–5 days/week of moderate to vigorous aerobic activity (this is the subject of a future forum).

- Stretch duration:

- Hold each stretch for 20–30 seconds. Don’t bounce. Bring it to the point where you feel the stretch, so you know you're doing something, but it's not painful.

- Strengthening:

- High weight / lower repetition. Ask your therapist or physician which muscles you need to strengthen.

- Endurance:

- Low weight / higher repetition.

REMEMBER:

-

Don’t do anything that causes pain. Your exercises are not meant to be painful.

-

If you can only do one thing and you have chronic pain, the most important thing to do is stretching.

Resource

Preservation of Upper Limb Function: What You Should Know A Guide for People with Spinal Cord Injury Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine and Paralyzed Veterans of America, by the Paralyzed Veterans of America Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Washington, DC: Paralyzed Veterans of America; 2008. Free downloadable copy is available at www.pva.org (click on "Publications" from the "Get Support" drop-down menu).

References

- American College of Sports Medicine position stand: the recommended quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness in healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1990;22:265–274

- Ballinger, DA, et al. The relation of shoulder pain and range-of-motion problems to functional limitations, disability, and perceived health of men with spinal cord injury: a multifaceted longitudinal study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81:1575–1581.

- Bayley, JC, et al. The weight-bearing shoulder: the impingement syndrome in paraplegics. J Bone Joint Surg Am.1987;69:676–678.

- Boninger, ML et al. Pushrim biomechanics and injury prevention in spinal cord injury: recommendations based on CULP-SCI investigations. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2005;42(3 Suppl 1):9–19.

- Burnham, RS, et al. Shoulder pain in wheelchair athletes: the role of muscle imbalance. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21:238–242.

- Curtis, KA, et al. Effect of a standard exercise protocol on shoulder pain in long-term wheelchair users. Spinal Cord.1999;37:421–429.

- Curtis, KA, et al. Shoulder pain in wheelchair users with tetraplegia and paraplegia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil.1999;80:453–457.

- Ditor DS, et al. Maintenance of exercise participation in individuals with SCI: effects on quality of life, stress and pain. Spinal Cord.2003: 41:446-450

- Escobedo EM, et al. MR imaging of rotator cuff tears in individuals with paraplegia. AJR Am J Roentgenol.1997;168:919–923

- Gagnon, D. et al. Electromyographic patterns of upper extremity muscles during sitting pivot transfers performed by individuals with spinal cord injury. J Electromyogr Kinesiol.2009;19:509–520.

- Gellman, H, et al. Late complications of the weight-bearing upper extremity in the paraplegic patient. Clin Orthop Relat Res.1988;233:132–135.

- Gerhart, KA, et al. Long-term spinal cord injury: functional changes over time. Arch Phys Med Rehabil.1993;74:1030–1034.

- Goldstein, B, et al. Rotator cuff repairs in individuals with paraplegia. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;76:316–322.

- Gutierrez, DD, et al. The relationship of shoulder pain intensity to quality of life, physical activity, and community participation in persons with paraplegia. J Spinal Cord Med.2007;30:251–255.

- Hicks, AL et al. Long-term exercise training in persons with spinal cord injury: effects on strength, arm ergometry performance and psychological well-being. Spinal Cord. 2003;41:34–43.

- Jacobs P, Nash M. Circuit training provides cardiorespiratory and strength benefits in persons with paraplegia. Journal of American College of Sports Medicine.2000; 711-717.

- Kulig, K, et al. The effect of level of spinal cord injury on shoulder joint kinetics during manual wheelchair propulsion. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2001;16:744–751.

- Lunqvist, C, et al. Spinal cord injuries: clinical, functional, and emotional status. Spine (Phila Pa 1976).1991;16:78–83.

- Lyons, PM. Orwin, JF. Rotator cuff tendinopathy and subacromial impingement syndrome. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30:S12–S17

- McCasland, LD, et al. Shoulder pain in the traumatically injured spinal cord patient: evaluation of risk factors and function. J Clin Rheumatol. 2006;12:179–186.

- Mulroy, SJ, et al. Strengthening and Optimal Movements for Painful Shoulders (STOMPS) in Chronic Spinal Cord Injury: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Phys Ther. 2011:91:305-324.

- Mulroy, SJ. Electromyographic activity of shoulder muscles during wheelchair propulsion by paraplegic persons.Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:187–193.

- Nash, MS, et al. Effects of circuit resistance training on fitness attributes and upper-extremity pain in middle-aged men with paraplegia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88:70–75.

- Nawoczenski, DA, et al. Clinical trial of exercise for shoulder pain in chronic spinal injury. Phys Ther.2006;86:1604–1618.

- Newsam, CJ, et al. Three dimensional upper extremity motion during manual wheelchair propulsion in men with different levels of spinal cord injury. Gait Posture. 1999;10:223–232.

- Paralyzed Veterans of America Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Preservation of Upper Limb Function Following Spinal Cord Injury: A Clinical Practice Guideline for Health-care Professionals.Washington, DC: Paralyzed Veterans of America; 2005.

- Pentland, WE, Twomey, LT. Upper limb function in persons with long term paraplegia and implications for independence: part I. Paraplegia.1994;32:211–218.

- Pentland, WE, Twomey, LT. Upper limb function in persons with long term paraplegia and implications for independence: part II. Paraplegia.1994;32:219–224.

- Perry,J, et al. Electromyographic analysis of the shoulder muscles during depression transfers in subjects with low-level paraplegia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:350–355.

- Popowitz, RL. Rotator cuff repair in spinal cord injury patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12:327–332.

- Reyes, ML, et al. Electromyographic analysis of shoulder muscles of men with low-level paraplegia during a weight relief raise. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76:433–439.

- Scelza WM, et al. Perceived Barriers to Exercise in People with Spinal Cord Injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005; 84: 576-583.

- Sie, IH, et al. Upper extremity pain in the postrehabilitation spinal cord injured patient. Arch Phys Med Rehabil.1992;73:44–48.

- Subbarao, JV, et al. Prevalence and impact of wrist and shoulder pain in patients with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med.1995;18:9–13.

- Thompson W. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Presription. 8th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincot Williams & Willis.; 2010 Shepard TH. Catalog of Teratogenic Agents. 7th ed. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press; 1992.

- Zemper et al. Assessment of a Holistic Wellness Program for Spinal Cord Injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2003; 82:957-968.