SCI Forum Reports

Picture this ... Pressure Mapping Assessment for Wheelchair Users

June 8, 2004

"You don't have to be injured with a Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) for very long to realize that your skin integrity is compromised," said Kendra Betz, PT, manager of the comprehensive Outpatient Physical Therapy Service and the Physical Therapy Clinical Education Program for the SCI Service at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System in Seattle, Washington. "Impaired circulation, sensation, and muscle contraction puts you at risk for pressure ulcers. Regardless of the diagnosis, any person with a neurologic injury whose ability to feel and move is altered is at risk for trauma to the skin and tissue beneath the skin."

A nationally-recognized specialist in the area of wheelchair seating and pressure mapping, Betz is known in her field for pressure mapping just about anything, including toilet seats and shower chairs, mattresses, vehicle seats and sports equipment.

Betz reported that pressure ulcer rates are high in at-risk populations: 23% of all nursing home residents and 60% of persons with SCI develop a pressure ulcer at some time.

"The cost of treating these pressure ulcers is enormous," she said. An advanced sore requiring hospitalization and surgery costs $70,000 or more; and between $3.5 and $7 million is spent each year on the treatment of pressure ulcers.

"More important is what skin breakdown means to you as a wheelchair user," Betz said. Dressing changes, close monitoring of skin, limited sitting time, and restriction of normal activities-including lost time from work-disrupt daily life for days, weeks, or even months. Complications such as wound infections can occur, which increase healing time and can lead to other medical issues. Dealing with a pressure ulcer can be discouraging, even depressing, especially if you worked very hard to take good care of your skin.

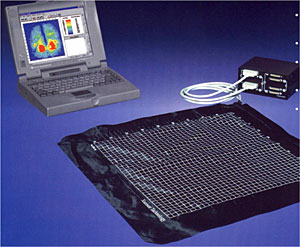

Pressure mapping technology (PMT) is an evaluation tool that consists of a computer, pressure mapping software, a flexible sensor pad, an electronics unit, and a power source. (See Figure 1.) Betz uses the Xsensor System, distributed by The Roho Group, Inc. The pad measures 18 by 18 inches and contains 1,296 individual capacitors (cells) that pick up signals when pressure is applied.

Figure 1: Pressure Mapping Technology (PMT) showing a computer with pressure mapping software, flexible sensor pad and electronics unit.

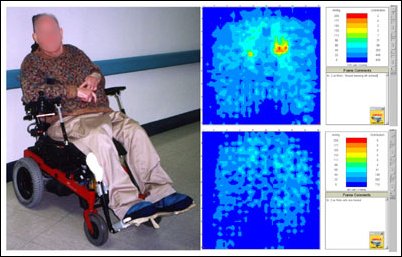

With the pad placed between the seat cushion and the person's buttocks, a digital reading of pressure information appears on the computer screen. The colors and numbers on the screen correspond to pressure readings expressed as millimeters of mercury (mmHg). Each cell has its own pressure reading value, so one image gives 1,296 separate readings. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2: Pressure map images show areas of high and low pressure while seated. The colors and numbers on the screen correspond to pressure readings expressed as millimeters of mercury (mmHg).

A key feature of this technology is the ability to adjust the sensitivity of the pressure reading. Values can be set between 10 to 200 mmHg; a higher level yields a higher pressure reading and shows more red on the digital image. "This is so important if you're comparing one pressure map to another," Betz said. To make comparison valid, they both must have the same sensitivity setting. "Lowering (the sensitivity setting) makes it look better (more blue, less red). You can't compare one map that's calibrated to 125 mmHg and one that's calibrated to 200 and try to draw inferences about which one is better for the individual. You need to compare apples to apples."

Figure 2 shows two pressure maps of the same client on two different cushions. The cushion on the right shows a better pressure map and perhaps a wiser choice for the client.

As good as PMT is, Betz stressed that it does not substitute for a "hands-on" seating assessment by a qualified clinician. "It's an addition to the interview and thorough evaluation findings and never substitutes for regular skin inspection."

While a pressure map can give important information about a specific individual sitting on a particular surface, the information cannot be generalized to other people or cushions, she said. "The same cushion under a different person gives completely different results. Be critical of cushion ads that show pictures of 'great' pressure maps. Pressure maps are always relative to the individual."

Pressure maps can demonstrate the variability among individuals using the same equipment. Figure 3 shows two different clients on the same cushion. The shorter, heavier patient (left) has good distribution, whereas the taller, leaner person (right) on the same cushion has a very different-and higher risk-result, demonstrating that "You cannot generalize about pressure maps from one person or one cushion to another," Betz said.

Figure 3: Two different subjects sitting on the same wheelchair cushion have very different results.

Further information can be obtained with the three-dimensional display option, seen in Figure 4. The "peaks and valleys" of a person's buttocks are evident in this display and resemble a topographic contour map. Peaks are the areas of highest pressure, often formed by the ischial tuberosities.

Figure 4: The three-dimensional display option provides further information about high-pressure areas of the buttocks. This case shows asymmetrical pressure, with high pressure on one side and low pressure on the other.

"The most valuable information for me is to look at specific cells and see where the highest pressure is and how pressure disperses around it," Betz said. Since the technology quantifies the amount of pressure in each cell, she gets objective feedback about how much she is able to improve pressure distribution each time she makes seating and cushion changes.

But again, values are relative. "Any particular value alone is not going to predict whether or not you get a sore," she said. "A whole lot of other factors have to go with it," such as posture, range of motion, strength, spasticity and movement. "Pressure mapping by itself does not provide enough information to come up with a treatment or seating plan."

Pressure mapping can be a powerful patient education tool. With a patient seated on the pressure pad, "I ask him to do a pressure release and let the patient see what happens on the map, which shows whether he's taking enough pressure off," Betz said. "I would like the patient to see when there is no contact across the seating area. The map shows whether we are getting down to zero pressure or we're just going from 200 to 175 mm of mercury."

Pressure mapping can help power wheelchair users determine how far back they must tilt their chairs to achieve effective pressure relief. Figure 5 shows a patient in three positions: upright and in a 45 degree and 45 degree tilt with recline. It is clear from the pressure maps that he must do the tilt with recline to get a good pressure release.

Figure 5: Pressure maps from left to right: upright; 45 degree tilt; 45 degree tilt with recline. The tilt with recline gives the best pressure relief in this case.

Pressure mapping helps guide the therapist in making equipment changes. In Figure 6, the simple addition of a wedge-shaped piece of foam provided better contact under the patient's thighs and, as a result, a healthier distribution of pressure, reducing the "hotspots" under the ischial tuberosities. "It is important to have full support under the thighs to distribute pressures away from bony areas. Typically, wheelchair users have more tissue at the back of their legs than they do under the pelvis." Betz said. "If your legs are not well supported, it increases pressure under the pelvis, which could result in a higher risk for a pressure sore there."

Figure 6: Pressure maps show pressure before (top) and after (bottom) adding a wedge to the patient's seating, improving distribution of pressure.

"I use pressure mapping to confirm what I think I already know," Betz said. "It's a fabulous tool and very valuable in making decisions, but there are limitations."

Pressure mapping measures vertical (up-and-down) interface pressure only. It does not measure friction or shear (side-to-side) forces, which can occur during transfers.

"And as most of you are aware, those forces are very major components of skin trauma and compromise. A person can have a beautiful pressure map while sitting still, but every time they transfer out of their chair they bump their rear end on their tire. You need to think about shear and friction as factors in skin health."

Pressure maps also do not measure skin temperature, moisture (from perspiration or urine), or general tissue health, all of which are significant factors in skin breakdown.

Pressure maps never substitute for skin inspection. "You can have an excellent pressure map and still have a skin issue or even a deep pressure wound," Betz noted. Pressure maps aren't a report card and don't tell a permanent story-they just capture a moment in time. "As years go by, our equipment ages, our bodies age, and our posture changes." The skin must be continually checked.

Besides pressure, other factors affecting skin health include nutrition, habits (smoking and drinking), how long a person has been injured (longer time means higher risk), medications, and overall health status.

In addition to wheelchair seating, Betz likes to use PMT for other seating surfaces. "I ask patients who come in with skin issues, 'how much time a day do you spend on your toilet seat? On your shower bench? What about bed positioning?'"

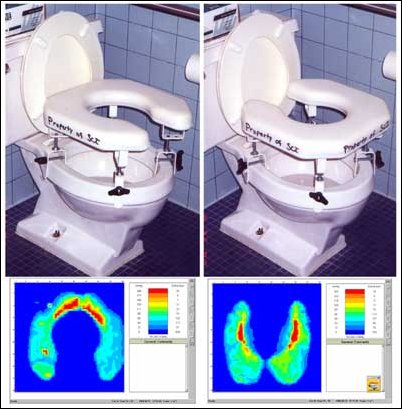

Figure 7 shows a patient with a pressure sore on his tailbone. The pressure map in his wheelchair was fine, Betz said. "But on the toilet seat you can see the problem. We did a simple intervention: we turned the toilet seat around so the opening is in the back instead of the front. We've shifted the pressure onto his hip bones - and we want to watch that - but we've taken the pressure completely off the active wound area."

Figure 7: On the left the high pressure areas are located in the tailbone area, where the patient had an active wound. Turning the toilet seat around (right) takes pressure off the wound.

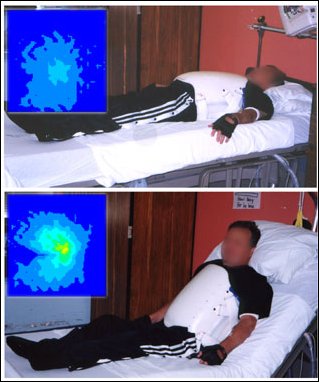

Bed positioning can be another problem. The patient in Figure 8 has a good pressure map while lying flat. When the head of the bed is elevated, however, there is pressure at the tailbone that could develop into a problem over time. "Even with the best mattresses out there, time spent sitting up in bed should be minimized," Betz said.

Figure 8: Pressure map while lying flat in bed is good (top) but gets worse when back rest is elevated.

Anyone who spends a lot of time in a car needs to be mindful of the vehicle seat. In Figure 9, the client's pressure map looks good in the wheelchair (bottom left), but sitting in the car a hotspot is evident at his tailbone (top right). Betz added a low-profile, air-inflated cushion to his car seat, and the resulting pressure map (bottom right) shows the improvement.

Figure 9: Pressure map in the wheelchair is good. In the car seat there is a red high pressure area (top right) that disappears when a cushion is added (bottom right).

Betz is adamant about airplane seating precautions as well: "Always sit on your cushion! You're in those seats a long time-you're the first one on the plane and the last one off. The airplane seats certainly were not designed for skin protection. Talk to your doctor or therapist about ordering a separate cushion for the plane and/or car and have them justify it (to the insurance company)." The pressure maps in Figure 10 show the client sitting in an airplane seat without a cushion (top) and with a cushion (bottom).

Figure 10: Pressure map while sitting in an airplane seat without a cushion (top) shows high pressure areas (red). Adding a cushion (bottom) reduces pressure on skin.

Betz also pays attention to time spent sitting in sports equipment. In Figure 11 the subject is seated in his handcycle with the standard foam cushion that comes with the equipment (top right). "The pressure map does not look good," Betz pointed out. "And it's difficult to do a pressure release while you're on a ride for several hours." She added a custom cushion to the handcycle seat and the results were excellent.

Figure 11: Pressure maps before (top) and after (bottom) adding a custom cushion to the handcycle seat.

Betz always asks patients about their usual sitting positions. "It's important to know if the way a patient is sitting during pressure mapping is the way he usually sits," she said. Positions such as one leg crossed over the other should be pressure-mapped if substantial time is spent that way.

Wound dressings can cause problems on the very skin they are supposed to protect. In Figure 12, Betz pressure-mapped a patient with and without the dressing. "It turned out the dressing added to the pressure," Betz said. "So if you have a wound that needs a dressing, the best place to be is off your bottom entirely."

Figure 12: Pressure map with (top) and without (bottom) a wound dressing. The dressing adds pressure to the wound.

Betz repeatedly emphasized that nothing should substitute for regular skin inspection. "The skin will not lie," she concluded. "If there's pressure, the skin will be discolored. If not, the skin will be normal. Skin inspection tells the story."